An excerpt from

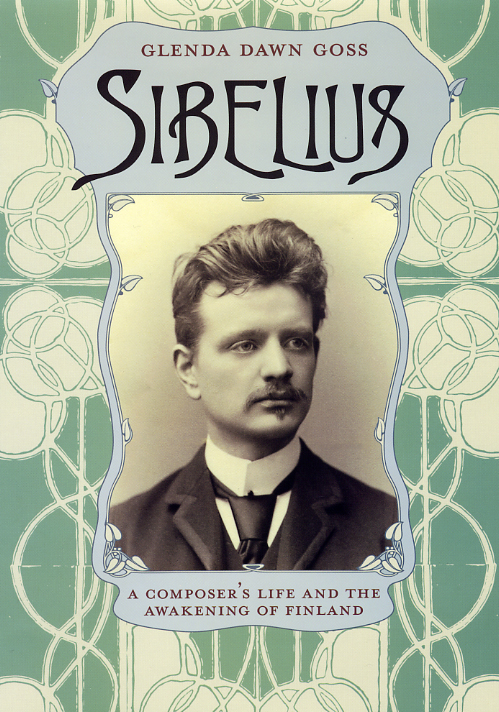

Sibelius

A Composer’s Life and the Awakening of Finland

Glenda Dawn Goss

An Unsolved Mystery

For those who appreciate elegantly solved mysteries, the strange case of composer Jean Sibelius and his lapse into silence has never been satisfactorily explained. The outline of his story goes something like this:

In a remote corner of a faraway land, a strangely gifted youth imagined music of such beauty and power that within his lifetime those imaginings became staple works of orchestras the world over. His sparkling violin concerto was well on its way to setting a record as the one most often recorded during the entire twentieth century. His symphonies and symphonic poems resonated in concert halls throughout the Nordic lands, across Europe, around England, and even in distant North America. Chamber works, solo songs, choral music, dramatic numbers, piano pieces all flowed from his pen.

Then the music stopped.

His supporters (for this is a man with decided proponents and opponents) say that the composer’s self-criticism grew to such proportions that it shut down his creative faculties completely (the self-criticism being somehow construed as bespeaking the great man’s modesty). His detractors point to the composer’s all-too-comfortable state pension and eventual prosperity or sagely nod their heads and murmur sanctimoniously about intemperance and the ill effects of unbridled consumption of alcohol.

Yet all these explanations leave a bad taste behind. On the one hand, the self-criticism argument forces one to ask how and why Sibelius differed from other creative artists who, throughout history, have exercised self-criticism of their own. On the other hand, the derogatory judgments fail to stand up to close scrutiny: Sibelius began receiving state support before a single one of his seven numbered symphonies was composed and without it might well have frittered all his time away in “sandwich pieces” to feed his growing brood of daughters. And can alcohol really be the explanation? After all, the composer lived well into his ninety-second year, to all appearances in good spirits (the psychological kind) and robust health.

Whatever the solution to this enigma, it is potentially of real importance, and not just to mystery lovers. It matters to all who are dismayed by the awful specter that human creativity is something that can be irretrievably lost.

The Scene of the Crime

Like any good detectives, then, we must visit the scene of the crime―in this case, Finland―and unearth buried clues; ask hard questions of those now silent witnesses such as newspapers, diaries, memoirs, and music manuscripts; and, not least, establish a sense of what has been called the geography of biography. Indeed, Finland’s geographical and botanical features―the woodlands and waterways, the flora and fauna that make up its natural world―have long dominated the image propagated of Sibelius and his music. “Apprenticeship of a Nature Lover” reads the opening chapter of a mid-twentieth-century Sibelius life story. From the words of his first biographer, Erik Furuhjelm, in 1915―“Sympathy for nature appears to be the primary, the Ur-characteristic of Sibelius”―to the Web pages of Finland’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs, where as recently as January 2006 Sibelius appeared (along with the Finnish architect Alvar Aalto) under the heading “National Identity in the Forests,” Sibelius has been represented as “firmly rooted in the forests,” his identity securely tied to the Finnish nation through its trees, flowers, birds, and lakeshores. Why, the very titles of his music prove the contention: from early settings of Finnish nature poems (Runeberg’s När sig våren åter föder [When Spring Once More Comes to Life]) to the last orchestral tone poem, Tapiola, which evokes the dwelling place of the forest god, a handful of undeniably great works along with a slew of little ones bear the names of Finnish trees, Finnish flowers, Finnish nature myths, and Finnish landscapes.

Yet the romanticized nature image conceals and distorts. In particular, it misrepresents geopolitical realities, since an essential part of that image is the notion of “little Finland,” a small nation in relation to the great powers of the world, albeit one that encompasses natural beauty, abundant natural resources, and a determined and heroic people. The same artificial and anachronistic notion continues in the refrain endlessly repeated in the country today, “Suomi on pieni maa” (Finland is just a small country).

The facts give a rather different picture. Territorially, present-day Finland is larger than the United Kingdom. Historically, Finland and its people were part of the kingdom of Sweden for six centuries (ca. 1155–1808/9), then belonged to Imperial Russia for more than one hundred years (1808/9–1917). Finland and its inhabitants have been formed as much by their symbiotic political relationships as by their natural environment. Being part of first one, then another enormous power relentlessly sculpted, altered, and shaped the country’s history, languages, and literature. Simultaneously, those same forces formed the unspoken attitudes, deepest assumptions, and creative manifestations of its people.

The scene of the crime thus reveals anything but a simple solution to the mystery. Instead, it forces us to consider an array of complicating factors, not least the roles of the powerful realms of Sweden and Russia, which throughout Sibelius’s lifetime and for centuries before that had molded his country. Sibelius spoke the language of the first realm, while living, until the age of fifty-two, as a citizen of the second. And he was born into these unusual surroundings at an exceedingly propitious time: music and the arts mattered. They were part of what Finns needed to formulate, demonstrate, and celebrate their golden ages of the past and create self-definition in the present vis-à-vis the great powers between which they were compressed.

Incited by the push-pull of the giants on either side of Finland, Sibelius and a handful of his predecessors and contemporaries set out to compose, conduct, draw, paint, poetize, sculpt, and versify what it meant to be Finnish, to inculcate a sense of pride in being Finnish, and through these activities to awaken their fellow Finns to their uniqueness, their separateness, and ultimately the possibilities of nationhood. They succeeded spectacularly, creating a world that so impressed its lustrous accomplishments upon those who encountered it that the epithet “golden age” was bestowed on their era and its artistic expressions. It was fitting that such a gilded epoch should have been born in regal surroundings―Imperial Russia, a realm of nearly unimaginable wealth and splendor. Of its surface glitter, Sibelius was supremely aware. He recognized it―and adored it. As he once wrote, “It’s the surface sparkle people fall for. But I love this sparkle, because when you march over worries and so on with a tiara on the back of your head, then life becomes so dramatic. Not this drab gray.”

To the extent that this golden age existed, a narrowly Finnish outlook was, paradoxically, not part of its character. Rather, during this time what was Finnish and what was more broadly European were inextricably mixed. It was also during this time that forces unforeseen by the creators of Finland’s golden age were awakened: a desire for equal rights, for better working conditions, for improvement in the daily lives of ordinary working people. It is said that children eat their fathers, and Finland’s revolutionary awakening was no different. In its train those who crafted its precepts and envisioned its artistic shapes either went into exile, were smothered into silence, or were turned into empty icons, all their creative juices sucked dry.

The hard truth about the Sibelius mystery, and one of the reasons for the difficulties in getting to the heart of it, is that this mystery compels us to confront things we would rather avoid for the sake of social or political correctness, such as class. The language of class difference permeates the correspondence of Sibelius and his contemporaries, colors their perceptions, and shapes their art. Such language raises hackles among many in “democratic” America, but without it we can have no meaningful discussion of Finland, its history, or its creative artists. We have to get over any squeamishness that might arise from speaking about nationalism, social class, linguistic prejudice, elitism (as in the arts), and, not least, the price of regime change, even when or especially when that change is to a democratic system, because all of these uncomfortable truths belong to the gritty reality of Sibelius and Finland’s story, a story that has acquired unusual currency in our time. Its significance goes beyond human curiosity about how other people lead their lives and how they solve the central problems of existence. In an era when regime change is promoted for the common good, it is important to understand all of its costs.

The difficulties are undeniable. Who would want to argue that in weighing the benefits of living in a militant democracy against those of living under increasingly autocratic emperors, the gain in human welfare of the one might come at the cost of the creative force engendered by the other? Yet the fact is that, with the series of events that culminated in the Bolshevik Revolution, Finland’s secession from Russia, and its launch into independence, Jean Sibelius’s creativity―like that of so many of his generational compatriots―came to an end. To be sure, the end came gradually. But come it did―within a mere ten years of the country’s declaration of nationhood.

However “self-critical” Sibelius may have been, to ignore the impact of the cultural and political climate on his and other creative minds is to leave out the most startling and important part of their story. As Sibelius once observed about himself, “I’m not suited for ‘writing’ music. All [music] has to be experienced.” Composers, writers, and artists inevitably reflect experiences on their home turf and its tensions in relation to the outer world to which they also belong, and where they travel. To understand Sibelius, to try and fathom the mystery of his lost creativity, mortifyingly played out on an international stage, requires understanding more fully the world from which he came. It is to that end that this book is written.

![]()

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 1–12 of Sibelius: A Composer's Life and the Awakening of Finland by Glenda Dawn Goss, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2009 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Glenda Dawn Goss

Sibelius: A Composer's Life and the Awakening of Finland

©2009, 496 pages, 8 color plates, 36 halftones, 47 musical examples, 7×10

Cloth $55.00 ISBN: 9780226304779

Also available as an e-book

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Sibelius.

See also:

- Our catalog of music titles

- Our catalog of biography titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog