An excerpt from

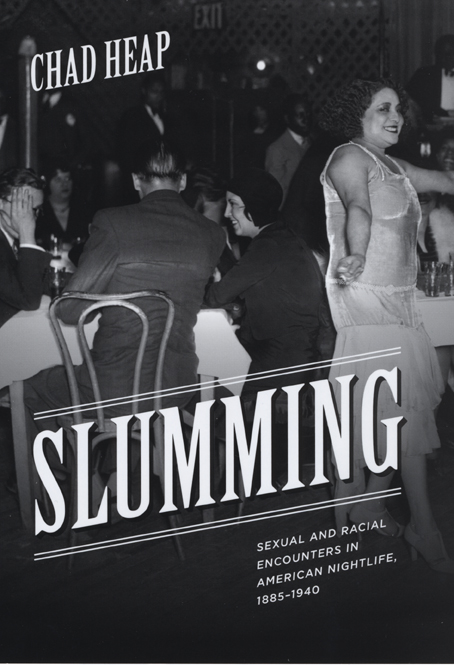

Slumming

Sexual and Racial Encounters in American Nightlife, 1885-1940

Chad Heap

Introduction

For most Americans, the notion of “slumming” conjures up images of well-to-do whites’ late-night excursions to the cabarets of Prohibition-era Harlem. Like the African American jazz chanteuse Bricktop, they likely recall a time when “Harlem was the ‘in’ place to go for music and booze,” and “every night the limousines pulled up to the corner,” disgorging celebrities and hundreds of other “rich whites … all dolled up in their furs and jewels.” The more socially and politically attuned might recollect scenes of interracial camaraderie, in which white jazz musicians and aficionados eagerly interacted with beloved black performers and patrons at Small’s Paradise or budding civil rights activists attended fundraisers for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) at the popular Lenox Club. Yet when Americans think about slumming, in all likelihood they imagine scenes that emphasize the more pejorative aspects of this once-popular cultural practice. Recalling Jim Crow establishments such as the Cotton Club and Connie’s Inn, they probably envision segregated crowds of inebriated, well-to-do “Nordics” being entertained by a host of scantily clad, light-skinned chorus girls and darker-skinned musicians. Or perhaps they imagine even more bawdy scenes, in which otherwise “respectable” white women and men ventured into Harlem’s lower-scale dives in search of supposedly more authentic black entertainment, cross-racial sexual encounters, and the anonymity necessary to allow themselves to indulge in the “primitive” behaviors and desires they associated with blacks.

From the best intentioned to the most horrifyingly exploitative, each of these scenarios depicts some aspect of what slumming has come to represent in U.S. cultural memory. But the tendency to remember this complex practice as a Prohibition-era, New York–centered encounter between whites and blacks hardly does justice to the crucial role slumming played in shaping the popular conceptualization of race, sexuality, and urban space in the United States over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The practice of slumming began some three decades before Prohibition became effective nationwide in 1920, and it persisted beyond well beyond the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1933. Moreover, while the U.S. version of slumming probably started in Manhattan and certainly reached its apogee in that city, in one form or another this cultural phenomenon materialized in every major U.S. urban center and many smaller ones, and its effects on the ways that Americans thought about urban life and the different types of people who resided in U.S. cities resonated even in the most sparsely populated areas of this sprawling nation.

The social dynamics of this voyeuristic, oft-demeaning but always revealing practice also extended well beyond the parameters of any preconceived notion of crossing a presumed white/black racial divide. From the mid-1880s until the outbreak of the Second World War, an overlapping progression of slumming vogues encouraged affluent white Americans to investigate a variety of socially marginalized urban neighborhoods and the diverse populations that inhabited them. In its earliest formulation, slumming prompted thousands of well-to-do whites to explore spaces associated with working-class southern and eastern European immigrants, Chinese immigrants, and blacks. But successive generations of such pleasure seekers set their sights instead on the tearooms of “free-loving” bohemian artists and radicals, the jazz cabarets of urban blacks, and the speakeasies and nightclubs associated with lesbians and gay men. As they did so, slummers gave lie to the commonly held notion that U.S. cities of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were little more than urban congeries of highly segregated racial and sexual communities. Moreover, they spurred the development of an array of new commercialized leisure spaces that simultaneously promoted social mixing and recast the sexual and racial landscape of American urban culture and space.

By focusing on the nightlife of New York and Chicago, this book delineates the crucial historical moment when slumming captured the popular imagination—and the pocketbooks—of well-to-do white Americans, demonstrating how this distinctive cultural practice transformed racial and sexual ideologies in the United States. As a heterosocial phenomenon through which substantial numbers of white middle-class women first joined their male counterparts to partake of urban leisure and public space, slumming provided a relatively comfortable means of negotiating the shifting contours of public gender relations and the spatial and demographic changes that restructured most U.S. cities during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Yet slumming accomplished more than simply creating places where affluent whites were encouraged to cross preconceived racial and sexual boundaries. By opening spaces where people could explore their sexual fantasies outside the social constraints of their own neighborhoods and where those who engaged in same-sex and cross-racial relationships could publicly express their desires, this popular phenomenon played an extensive role in the proliferation of new sexual and racial identities. In charting the full range of such complex cultural dynamics over a period of more than five decades, this book argues that slumming contributed significantly to the emergence and codification of a new twentieth-century hegemonic social order—one that was structured primarily around an increasingly polarized white/black racial axis and a hetero/homo sexual binary that were defined in reciprocal relationship to one another.

When well-to-do whites went slumming in turn-of-the-century U.S. cities, crossing the neighborhood boundaries that separated their daily lives from the urban poor, they built on a long tradition of similar excursions. Since at least the mid-1830s, New York’s wealthier residents and occasional sightseers regularly visited impoverished urban areas, such as the lower Manhattan neighborhood known as Five Points. Like later-nineteenth-century slumming parties, these early visitors walked the streets and examined the hovels and low-down dives of immigrant and working-class New York. But in several important respects, their explorations of urban poverty and immorality differed from the slumming excursions that became so popular in New York and Chicago over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. First, in the mixed landscape of the mid-nineteenth-century walking city, where the homes of affluent and poor were jumbled together in close proximity not only with each other but also with a variety of commercial enterprises, these early ramblings usually covered no more than a few blocks. As such, they were more investigations of pockets of degradation and illicit activities in affluent whites’ own neighborhoods than ventures into separate urban districts. Only after the mid-1850s, but especially during the Gilded Age building boom that followed the Civil War, did this relatively integrated urban environment give way to the increasingly hierarchical arrangement of urban culture and space, which provided the basis for affluent whites to imagine their journeys into immigrant and working-class New York neighborhoods as slumming excursions into wholly distinct—even foreign—urban districts. In the younger city of Chicago this requisite reorganization of urban space occurred even slightly later, during the massive reconstruction efforts undertaken following the famous 1871 conflagration.

The cultural context of mid-nineteenth-century journeys into the immigrant and working-class sections of New York and Chicago also set them apart from later slumming excursions. Although some mid-nineteenth-century New Yorkers and Chicagoans clearly ventured into these areas simply to satisfy their curiosity about local social and moral conditions, the vast majority of the women and men who toured Five Points and similar districts in Chicago did so in conjunction with two well-defined urban institutions: the evangelical Protestant moral reform movement and the more boisterous, class-integrated sporting culture of urban men.

At a time when a new white middle-class ideology of separate spheres required women to structure their lives around hearth and home, fundamentally ceding the public realm of the city to men, the moral reform work carried out by evangelical Protestants provided mid-nineteenth-century women with their only respectable entre into urban working-class life. To preserve their good reputations, under nearly all circumstances “respectable” women steered clear of poverty-stricken urban neighborhoods, rarely venturing into public at all without a male escort, in order to distance themselves from any association with “public women,” or prostitutes. But because the Protestant reform movement drew upon women’s domestic expertise, it provided an opportunity for religious-minded women to carve out a public role for themselves, undertaking a series of “home visits” to local tenements to teach immigrant and workingwomen the “proper” methods of housekeeping and child rearing. Other female reformers called upon their reputations for religious piety to address the moral conditions of the cities’ tenement districts. Descending upon local brothels in the company of like-minded men, they launched a program of “active visiting,” endeavoring to convert local prostitutes to their particular brand of Christianity and providing refuge in newly founded missions and safe houses to those women whom they were able to coax away from the demimonde. Yet even though this work encouraged white middle-class women to interact with the urban underworld, its religious impetus and accomplishments clearly set such cross-class encounters apart from those that would come to characterize slumming at the century’s end.

The sporting culture of mid-nineteenth-century New York and Chicago shared even more in common with slumming, but it, too, differed in significant ways. Organized around access to liquor, gambling, pugilism, and cockfighting, sporting-male culture provided a means for white middle- and upper-class men to join their working-class brethren in the rough-and-tumble environs of the Bowery and comparable working-class districts in Chicago. Yet even as such interactions promoted a sense of fraternity and mutual respect among a wide range of urban men, the possibilities that the sporting life presented for crossing the social and cultural boundaries of the city remained restricted almost entirely to the male domain. Grounded in an atmosphere of rowdy male homosociality, sporting-male culture usually permitted the entry of women only if they were sexually available and never if they insisted upon maintaining a sense of decorum and respectability. In fact, as important as drinking and gambling were to the establishment of a sense of cross-class camaraderie, that camaraderie’s very existence was maintained in large part by men’s shared access to the sexual favors and paid services of working-class women. Such interactions persisted, of course, with the advent of slumming in the mid-1880s. But because the latter practice was part and parcel of the increasing heterosocialization of urban leisure, in which the public dance hall and other “cheap amusements” supplanted the all-male environs of the saloon, it afforded respectable women of all classes with a range of new opportunities for crossing the social and cultural boundaries of the city. Participating in New York’s nascent bohemian subculture of writers, actors, and artists, a handful of actresses and society matrons got a jumpstart on this trend during the 1870s, visiting Chinatown opium dens and popular Bowery and Tenderloin concert halls. But for most affluent white women in Chicago and New York, the chance to partake of such pleasure-oriented excursions into the cities’ immigrant and working-class districts became available only at the end of the nineteenth century.

To a significant degree, then, the practice of slumming emerged from the consolidation of these two earlier traditions of cross-cultural encounter, combining the reform movement’s engagement of respectable white middle-class women with the sporting-male culture’s unabashed pursuit of pleasure. Indeed, in its earliest formulations, the very notion of slumming often retained some sense of the benevolent work undertaken by nineteenth-century female reformers. Such was certainly the case when an 1888 tract on female and child labor reported that “Mrs. Dr. Clinton Locke … has, perhaps, done more real charity for the Chicago poor” by going “‘slumming’ … into the holes and hovels … where she personally taught ignorant Irish, Polish, Swedish, German, and Italian mothers how to make broth from scraps, gruels from chaff, and tempting cookies from cheap flours.” But as an increasing number of well-to-do whites set out to “do the slums” of New York and Chicago, the popular definition and practice of slumming shifted more definitively toward the pursuit of amusement. In an emerging heterosocial permutation of the earlier sporting-male culture, slumming actively encouraged middle- and upper-class white women to join their husbands, boyfriends, and brothers as active participants in the rambunctious environs of the cities’ immigrant and working-class resorts.

Yet this new cultural practice accomplished more than simply opening a previously all-male realm of cross-cultural camaraderie to so-called respectable white women. It also served as a mechanism through which affluent whites could negotiate the changing demographic characteristics and spatial organization of modern U.S. cities. Encompassing an even broader cultural terrain than its predecessors, slumming became central to the emergence of the commercialized leisure industry, prompting the creation of a variety of new public amusements that promoted the crossing of racial and sexual boundaries. This development in turn fueled the advent of more intense urban reform campaigns that were designed to police the cross-cultural and sexual interactions that took place in these spaces and to reinforce traditional nineteenth-century notions of social and sexual propriety and respectability. But as reformers fought an uphill—and ultimately unwinnable—battle, white middle- and upper-class New Yorkers and Chicagoans began to embrace slumming even more heartily—not only as a means to ground the changing popular conceptualization of race and sexuality in particular urban spaces but also as an opportunity to shore up their own superior standing in the shifting racial and sexual hierarchies by juxtaposing themselves with the women and men that they encountered on their slumming excursions.

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were a highly contentious period in U.S. history. The rapid urbanization of an increasingly varied and expanding population—exemplified by the massive immigration of southern and eastern Europeans and the unprecedented migration of Southern blacks and single women and men to American cities—created a sense of tremendous flux. Indeed, the very basis of American nationality was openly and vociferously debated. Historians have described the antagonistic efforts undertaken by so-called old stock Americans—those of northwestern European descent—to solidify the boundaries that separated them from the supposed danger posed by these new urban populations. An ever-expanding array of public and private reform organizations battled to control the moral construction of the urban landscape, stigmatizing and criminalizing the social and sexual behavior of immigrants, blacks, and single women and men, while attempting to Americanize them through the imposition of the standards of middle-class respectability.

U.S. cities were also marred by the rebirth of particularly virulent strains of nativism and racism. The Red Scare that followed the First World War painted Italian and Russian—especially Jewish—immigrants as potent, socialistic threats to the Anglo-American way of life. Native-born whites led a campaign for legislative quotas, slowing eastern and southern European immigration to a trickle and completely excluding the entry of Asian immigrants into the United States. During this same period, the Ku Klux Klan experienced dramatic growth, especially in northern U.S. cities, where the animosity of its estimated four to five million members was directed primarily against adherents to the “alien” religions of Catholicism and Judaism. The Klan’s historical reign of violence against African Americans also continued; lynchings occurred with frightening frequency well into the 1930s, enforcing racial, class, and gendered hierarchies of power through sheer force of terror. When Southern blacks migrated to northern cities in search of better economic and social conditions, they were greeted with still more violence—at the workplace, in the streets, and in an extraordinary wave of urban riots during the late 1910s and early 1920s.

The hostility of old-stock Americans was also directed at the single women and men who flooded U.S. cities during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Although the women’s suffrage movement overcame strong opposition to achieve passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, its supporters were increasingly lesbian-baited because of their expressed opposition to women’s traditional roles. Other “New Women,” single men, and urban bohemians were castigated for their supposed sexual immorality and promiscuity. Their support for birth control measures, engagement in sexual relations for pleasure, and other transgressions against reproductive sexuality rendered them social outcasts on par with prostitutes and so-called sexual inverts.

Such developments marked the extremes in the struggle to maintain or reorganize the structure of power in early-twentieth-century U.S. cities, but similar battles occurred on a daily basis in the more mundane reaches of urban life—on neighborhood streets, for example, and in local workplaces, housing, and public amusements. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the slumming venues of New York and Chicago furnished a unique space for such everyday struggles by encouraging middle- and upper-class whites to choose to interact with the women and men who lived in the cities’ socially marginalized districts. In the absence of any fixed biological or cultural notions of race and sexuality, this decision to go slumming provided a powerful means to naturalize changing notions of racial and sexual difference by “marking” them into the material culture and physical spaces of U.S. cities. That is, as well-to-do whites interacted with the inhabitants of increasingly racialized and sexualized urban neighborhoods, slumming made the abstractions of race and sexuality seem more stable and “real.”

This book’s first two chapters trace the spatial dimensions of this phenomenon, documenting both the shifting cultural geography of slumming and the range of regulatory mechanisms that white middle-class reformers and municipal officials devised to police the social and sexual interactions that took place in these spaces. Concocted as a way for well-to-do whites to observe and sometimes interact with the most “foreign” residents of late-nineteenth-century New York and Chicago, slumming began as a place-based activity focused on the so-called slums and red-light districts inhabited by recent southern and eastern European immigrants, blacks, and Chinese. Yet even as this unique cultural practice prompted affluent whites to participate in the bustling public culture of these districts, it also reified the notion of the slum as a container for the degradation and immorality commonly associated with such racialized populations. However, when reformers successfully effected the closure of the cities’ red-light districts in the early- to mid-1910s, slumming became detached from the specific urban locale of the slum and assumed the status of an activity in and of itself. Rather than describing affluent white pleasure seekers’ participation in the dance halls and saloons of the cities’ immigrant and working-class districts, slumming became a type of amusement that they used to negotiate subsequent demographic and spatial changes in the city. As sizable new populations of “free-loving” bohemian artists and radicals, blacks, and lesbians and gay men appeared in New York and Chicago, they each became the subjects of successive new slumming vogues. These vogues in turn helped to associate each of the new populations with particular urban spaces, simultaneously establishing them in the public’s mind as exotic others—as the residents of the immigrant and working-class districts before them had been—while downgrading the urban spaces with which they were associated by casting them in terms of the slum.

Building on this cultural geography, the final four chapters of this book critically examine the everyday racial and sexual negotiations that took place among the participants during each of four successive slumming vogues. Beginning with affluent whites’ turn-of-the-century excursions into the slums and red-light districts of Chicago and New York, the chapters focus sequentially on slummers’ search for “bohemian thrillage,” their increasing fascination with the “Negro vogue,” and the emergence of the “pansy and lesbian craze.” From the mid-1880s until the outbreak of the Second World War, these vogues prompted the development of a range of public amusements where the ongoing transformation of racial and sexual ideologies in the United States could be intimately experienced and where participants were encouraged to use their slumming excursions to mark emerging conceptions of race and sexuality in the popular culture and space of U.S. cities.

As recent historical studies by Mathew Frye Jacobson, Robert Orsi, David R. Roediger and others have demonstrated, the residents of late-nineteenth-century U.S. cities had a very different perception of “race” and racial difference from that which would become hegemonic by the middle of the twentieth century. Rather than viewing all individuals as either white or black, they operated within a racial framework that cast recent immigrants from southern and eastern Europe—especially Italians and Jews—as a sort of nonwhite “in-between” group of peoples, situated above blacks in the racial hierarchy of the United States but beneath old-stock whites. They likewise possessed a different understanding of sexual normalcy and difference than that defined by the hetero/homo sexual dyad that also consolidated its cultural hegemony in the mid-twentieth century. As scholars such as George Chauncey, Lisa Duggan, and Jonathan Ned Katz have shown, in the late nineteenth century—and among many immigrant and working-class communities well into the first decades of the twentieth century—sexual abnormality was defined not by the expression of one’s sexual desire for a person of the same sex but by one’s adoption of the mannerisms, public comportment, and even sexual roles commonly associated with members of the so-called opposite sex. That is, “mannish women” and feminine male “fairies” were considered to be sexually abnormal, but their more normatively gendered sexual partners were not. Feminine women and masculine men who abided by the sexual and other cultural roles conventionally ascribed to their sex could engage in same-sex sexual encounters without risking stigmatization or the loss of their status as purportedly normal women and men.

Mapping the complex relationship between racial formation and sexual classification in the United States over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this book details the crucial role that slumming played both in making visible and in facilitating the transition from one racial and sexual regime to the next. In addition, it demonstrates that the transformation from a gendered sexual regime to the now-hegemonic hetero/homo sexual binary was inextricably linked to the emergence of an increasingly polarized white/black racial axis—and vice versa. As successive slumming vogues encouraged affluent white women and men to position themselves in relation to a shifting series of racial and sexual “others,” slumming provided a mechanism through which its participants could use both race and sexual encounters to mediate their transition from one system of sexual classification to another. Moreover, by creating spaces where Jewish and Italian immigrants could begin to consolidate their claim to whiteness by simultaneously emulating and differentiating themselves from the sexual permissiveness and “primitivism” they had come to associate with black urban culture, slumming also ensured that shifting notions of sexual propriety and respectability became integral to the definition of race. That is, despite its occasional egalitarian impulses, slumming proved to be largely complicit both in the efforts of previously nonwhite or “in-between” racial groups to secure whiteness at the expense of black subjugation and in the refashioning of sexual normalcy and difference from a gendered system of marginalized fairies and mannish women to a cultural dyad that privileged heterosexual object choice.

![]()

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 1–11 of Slumming: Sexual and Racial Encounters in American Nightlife, 1885-1940 by Chad Heap, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2009 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Chad Heap

Slumming: Sexual and Racial Encounters in American Nightlife, 1885-1940

©2009, 432 pages, 19 halftones, 7 maps

Cloth $35.00 ISBN: 9780226322438

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Slumming.

See also:

- More titles in the Historical Studies of Urban America series

- Our catalog of history titles

- Our catalog of American studies titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog