The Introduction to

Terror and Wonder

Architecture in a Tumultuous Age

Blair Kamin

Introduction

For a journalist, there is no more precious commodity than time. Deadlines once were daily. Now, if you blog, as I do, they bear down almost hourly, permitting even less chance for careful reflection than in the hoary, pre-blogging days of, say, 1999. Against that backdrop of relentless pressure, the opportunity to put together this book was the ultimate luxury, allowing me to collect my thoughts as well as my columns. The exercise has allowed me to look back on an incredible era of striking buildings and cataclysmic events, which are recent enough to remain vivid in the memory but distant enough to be seen with the sort of clarity that daily journalism rarely permits.

Inevitably, I think back to the morning of September 11, 2001, and picture an editor rushing to my desk, where I was already furiously typing a story about the attack on the World Trade Center for an extra edition of the Chicago Tribune. When the editor told me that the first of the twin towers had collapsed, the shock was visceral. This was no distant disaster. Growing up in the small town of Fair Haven, New Jersey, I had gazed at the big, glinting boxes of the World Trade Center from the beaches of Sandy Hook, a thin, windswept peninsula whose northern tip is less than 16 miles from Lower Manhattan. From that vantage point, the twin towers had seemed as permanent as the Pyramids. Now one was gone, and the other would soon follow—the first time that iconic skyscrapers had vanished from the sky.

But I can conjure up an equally powerful recollection of the raucous scenes that accompanied the opening of Chicago’s Millennium Park on July 16, 2004. On that day, the city’s children discovered the twin glass-block towers of the Crown Fountain, where human faces projected on LED screens spewed jets of water on the kids, like modern versions of medieval gargoyles. The picture was sheer delight—an instant piazza. It was as if the joy-inspiring fountain had been created to help dispel the gloom induced by the destruction of the World Trade Center. After the short-lived, post-9/11 phenomenon of “cocooning,” in which terrified Americans found sanctuary in their homes, Millennium Park’s debut marked a triumphant return to, and restoration of, the public realm.

This book, which assembles 51 of my columns from the Tribune and other publications, brings together such stories to accomplish what they cannot do by themselves: to reveal the arc of a tumultuous epoch and to shed fresh light on some of its most significant works of architecture as well as the culture that produced them. How did what we built reflect and affect how we lived? Where did we make superlative art, and where did we scar our cityscapes? Where did we overbuild, and where did we underperform in our role as stewards of the natural and built environments? And, above all, how can a better understanding of this complex and contradictory era help us avoid repeating its worst mistakes?

The columns examine buildings and public spaces throughout the United States—from New York to Los Angeles, New Orleans to Milwaukee—with a special emphasis on Chicago, the first city of American architecture, and one detour outside the country to the debt-ridden Persian Gulf emirate of Dubai. While the places are almost exclusively American, many of the architectural players and the themes their work raises are global, reflecting the rapid internationalization of the field. In these years, even third-tier American cities imported architectural stars from abroad to design major civic buildings. Conversely, U.S. firms exported their expertise in commercial architecture, particularly the skyscraper, to booming countries like China or city-states like Dubai.

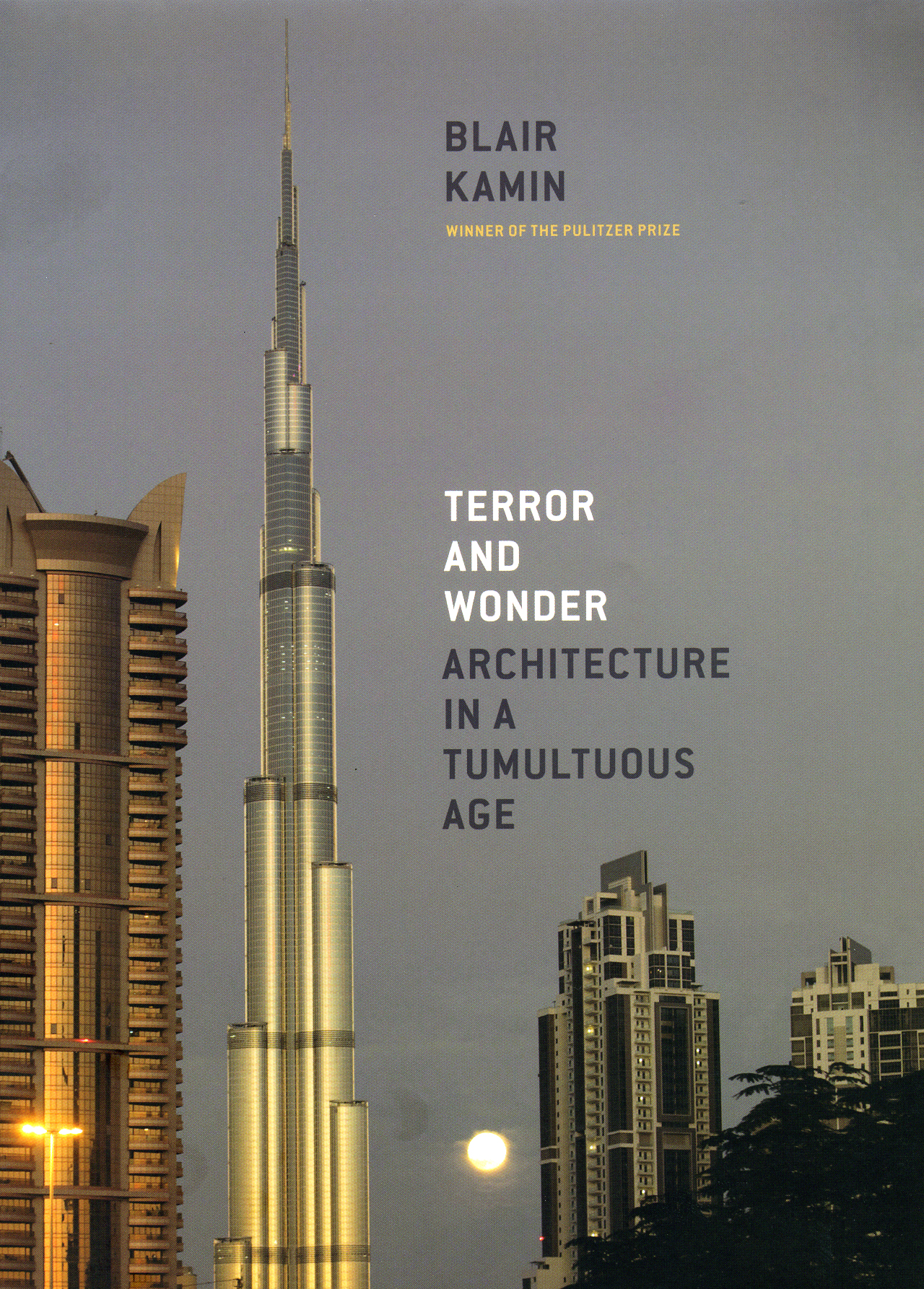

Considered chronologically, the columns are bracketed by two great thunderclaps in the sky—the destruction of the World Trade Center in 2001 and the opening of the Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building, which rose a staggering half mile above Dubai’s desert floor, in 2010. As the columns reveal, this was an era of extreme oscillation—between artistic and urban disaster, teeming public spaces and repressive security measures, frugal energy-saving architecture and giddy design excess, luxury-laced McMansions and impoverished public works, great expectations for rebuilding and painfully unrealized hopes. It was a Dickensian construction zone, a time of terror and wonder, with seemingly endless capacity to shock and surprise. And buildings were central to its narrative.

In these years, in addition to the stunning vertical plunge of the twin towers, the nation witnessed the sickening horizontal tableau of nearly an entire American city, New Orleans, under water. In response to the terrorist attacks, a new security apparatus encroached upon the mobility embodied by America’s airports and the ability of its government buildings to serve as vibrant centers of community. A housing bubble grew bigger and bigger until it inevitably burst, helping bring down the economy and leaving dreams for grandiose skyscrapers, such as Santiago Calatrava’s twisting Chicago Spire, as nothing more than holes in the ground.

And yet, not everything in these years ended in disarray. In addition to the exuberant landscape of Millennium Park, an extraordinary collection of cultural buildings by such architects as Frank Gehry and Renzo Piano provided new focal points for urban life. The push for an energy-saving “green architecture” moved from the fringes of American society to the mainstream, where it promised not only to reduce global warming but also to create more humane environments inside homes and workplaces. And with Barack Obama’s election to the presidency, that clumsy word “infrastructure” moved decisively into the public conversation, as the nation finally began to redress its shameful lack of attention to the unheralded but essential networks of transportation, water, and power that undergird all of modern life.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Chicago’s master of steel-and-glass modernism, once declared, “Architecture is the will of an epoch translated into space.” Yet even this cursory review of events suggests that there was no single direction to this epoch, but a series of cross-currents and counterrevolutions pulling in different directions at once. Nor was there any consensus on the right path for architects to take. Indeed, architectural culture, with its bitter divisions between aesthetic radicals and traditionalists (“the rads and the trads,” as Robert Campbell, my colleague at the Boston Globe, cheekily calls them), was as deeply polarized as the broader culture, with its split between red-state and blue-state America.

There were, however, broad themes that characterized this period, and they provide the organization for this book. Its five parts discuss, respectively, the state of cities in the aftermath of the 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina disasters; the fevered residential and commercial building boom; the equally frenzied construction of iconic cultural and campus buildings; the changing face of historic preservation and the rise of green architecture; and the beginnings of a new era, crystallized by Obama’s election, in which fresh ideas about infrastructure and other long-ignored issues came to the fore. Brief introductions situate the parts within the book’s overall framework, and postscripts follow many of the columns. I have edited the columns, shortening and sharpening them, but I have changed none of the opinions. Architecture criticism, like architecture, is an act of construction. Arranging the columns—seeing where they unexpectedly snapped together like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle—has been a process of discovery.

One of the most fascinating parts of the story is what didn’t happen after September 11, both to the culture at large and to architecture in particular. After the shock of 9/11, opinion leaders such as Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter and Time magazine’s Roger Rosenblatt portentously declared “the end of irony.” Soon after, Carter backtracked and said (ironically) that he actually had been talking about “the end of ironing.” Just as irony declined to die, so the skyscraper did not succumb to the terrorist threat, as some real estate developers and architecture critics had predicted it would. Instead, as the fear from the attacks ebbed and an unfounded exuberance took hold, the world experienced the greatest skyscraper building boom in history, with more towers rising to a greater height, in a wider variety of places, and with greater formal invention, than ever before.

But there was also something called the “new normalcy,” and it was plainly—and painfully—evident in the security lines choking airports and in the ugly Jersey barriers that popped up in front of everything from Sears (now Willis) Tower in Chicago to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC. Even the managers of the Rookery, the muscular Burnham & Root office building on Chicago’s LaSalle Street, shut its gossamer-light atrium to tourists, as if an 11-story, brownstone-covered landmark was actually going to be on Al-Qaeda’s hit list.

Why this overreaction? It had to do, in retrospect, with a central theme of the era: spectacle. The dictionary defines spectacle as a dazzling display, something remarkable to be seen or viewed. In a fiendish, twisted way, the terrorist attacks of 9/11 fit this definition precisely. They were emblems of spectacular destruction. By toppling iconic buildings—totemic symbols of American financial might and technological prowess—the terrorists succeeded in instilling deep-seated fears and destabilizing everyday life. A response was clearly needed, given the threat to national security that the attacks posed, but the ensuing reaction was overwrought, adding self-inflicted damage to the devastation already wreaked by the terrorists. It came in a new wave of fortress architecture that disfigured public spaces, transportation hubs, and government buildings—and promised to mar the very skyscraper, the Freedom Tower (now called I World Trade Center), that was rising in place of the destroyed twin towers.

The new museums of these years more easily fit the conventional definition of spectacle. They were like fireworks blazing across the sky, fully intent upon knocking your eyes out. Calatrava’s crowd-pleasing addition to the Milwaukee Art Museum, which flaunted a 217-foot-wide sunshade that unfurled like the wings of a giant bird, exemplified the type. This was architecture as entertainment, an urban event. Enabled by the latest computer technology, as well as advances in materials and construction methods, the spectacle buildings burst the traditional, rectilinear boundaries of architecture to make aesthetic statements that were more baroque than classical—and, above all, distinctly personal rather than anonymous. As if to underscore this phenomenon, Milwaukeeans referred to the museum addition as simply “The Calatrava.”

As the world became more generic, with stores and banks in one city resembling stores and banks in every other city, the spectacle buildings were increasingly what distinguished cities from one another. At best, as in Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, they uplifted their environs and created interiors that were stirring expressions of democracy. Far less satisfying were designs like Daniel Libeskind’s addition to the Denver Art Museum, a striking but self-indulgent structure that plainly elevated form over function.

However they turned out, spectacular or subtle, far too many of these cultural buildings saddled their institutions with financial burdens that proved difficult to bear. Some also proved unable to replicate the tourist-magnet magic of Gehry’s 1997 Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, and its so-called “Bilbao effect.” A little-noticed pattern repeated after architecture critics cheered each building’s opening and then departed for the next extravaganza: attendance and revenues didn’t match projections, and once the recession dramatically reduced the value of endowments, the sponsors of the new edifices were forced to lay off staff and cut hours as well as operating expenses. At Steven Holl’s partly underground addition to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, cost-cutting literally meant dimming the beauty of the addition’s proudest feature—the glass pavilions, or lenses, that drew daylight into the galleries and shone like jewels at night—for 14 hours per week. If you built it, they didn’t necessarily come.

This pattern of expansion and retrenchment was part of the much-noted phenomenon of overbuilding, symbolized by the foreclosure signs tacked onto exurban starter homes. Yet such excess was also evident in the nation’s frozen-in-place skylines, most notably Chicago’s. In the summer of 2007, when the stock market soared to new peaks, Chicago’s builders were poised to do the same, with three mega-towers—the 2,000-foot-tall Chicago Spire, the 1,361-foot Trump International Hotel & Tower, and the 1,047-foot Waterview Tower—under construction simultaneously. A little more than a year later, amid the stock market collapse and the credit crunch, work on the Spire stopped and the building of the Waterview Tower halted at its 26th story, leaving its hulking concrete frame looming over the Chicago River. Only the Trump Tower reached completion, and it was no financial home run, with roughly of a third of the skyscraper, including its 14,260-square-foot, $30 million penthouse, empty upon opening.

The saga of the three mega-towers hints at the vast extent of the building boom and its double-edged impact on cityscapes nationwide. In the 10 years ending in 2008, Chicago’s developers completed or started construction on nearly 200 high-rises—more than twice as many as in all of nearby Milwaukee. True, those high-rises created a healthy urban density, allowing more people to walk to jobs and shops. Yet far too many of them were stark slabs plopped atop blank-walled parking-garage podiums. For all the media buzz about star architects turning out “starchitect condos,” the Chicago boom was, in reality, a two-track production line, in which top talents created rare successes, such as Jeanne Gang’s marvelously curvaceous Aqua tower, while hacks cranked out pervasive architectural junk.

Even the tiny branch banks that financed the housing bubble were eyesores. And the boom wrought new forms of destruction on old buildings, from the demolition of mid-20th-century modernist landmarks to the “facade-ectomies” that saved nothing more than thin pieces of historic structures, like a slice of prosciutto. In London’s St. Paul’s Church, the epitaph for Sir Christopher Wren famously reads: “Si Monumentum Requiris, Circumspice”—“If you would seek his monument, look around you.” In the post-crash America of 2010, our architectural and urban planning mistakes are all around us.

At the same time, beneath the surface of the glitter and the visual dreck, a countervailing force was gathering—a new push for sustainability, a word that once simply meant “capable of being sustained,” but increasingly took on ecological overtones. Rooted in concern that buildings account for almost half of the greenhouse gases in the United States, the new sustainable, or green, architecture made a startling ascent. At the beginning of the decade, it was rare for architects to concern themselves with energy efficiency and environmentally friendly building materials. By the end of these years, such attentiveness to architecture’s environmental consequences, while by no means universal, was happening more and more. In an unmistakable sign of green design’s growing popular appeal, crafty developers flaunted their buildings’ sustainable credentials as a marketing tool while in some cases environmental awareness devolved into “green sheen.” My favorite example: the planted roof of a showcase McDonald’s in Chicago. Putting some shrubs and grass atop such a symbol of the energy-wasting car culture was like slapping a piece of lettuce on a bacon double cheeseburger and calling it healthy.

In contrast to the spectacle buildings, which bore the branded looks of individual stars, the movement for sustainability was by its very nature a collective enterprise, focused on the environment as a whole rather than stand-alone architectural objects. Its proponents dwelled less on architectural form than building performance, deemphasizing the architectural dazzle of today in favor of saving the planet for tomorrow.

In the broadest sense, sustainability was not simply about being green, but about reasserting values that were missing or overlooked during the boom years—practicality rather than profligacy, modesty rather than vanity, humility rather than hubris, enduring quality rather than evanescent bling. The infrastructure portion of Obama’s $787 billion stimulus package, which funded the weatherization of modest-income homes and rehabs that made federal buildings more energy efficient, reflected and began to restore those values. Yet, unexpectedly, so did a building like Gang’s Aqua, which wasn’t simply alluring because of its spectacularly undulating balconies. It was beautiful because it put 738 apartments and condominiums within minutes of workplaces, shops, and entertainment, reducing their residents’ reliance on energy-wasting driving. In architecture, as in life, true beauty is more than skin-deep.

My aim, as such examples are intended to suggest, is not to construct this story as a two-dimensional morality play, in which “spectacle” is bad and “sustainable” is good. There is no simple formula for architectural creativity or building vibrant cities. An iconic building can be sustainable just as a sustainable building can be an eyesore. It is even possible for architects to make a spectacle of sustainability, transforming energy-saving features into over-the-top, formal flourishes. What counts in the end are not good intentions but good buildings. The current intellectual fashion, which has critics lumping together the masterpieces and the mediocrities of these years under the facile rubric of “The Decade of Excess,” will, I suspect, prove as shortsighted as the attempts to dismiss the exuberant art deco architecture of the 1920s after the stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression. Art endures. And so does architectural quality; the character of the work matters more than foibles of the era that produced it. The point is not to rid the world of spectacle buildings; the point is that cities and urban regions based on spectacle alone cannot sustain themselves. A new century and new circumstances demand a new architectural ethic, one that brings the opposing approaches of spectacle and sustainability into better balance.

The real issue, in the end, is not technical or even aesthetic but cultural. It’s about how we live, not how many British thermal units a new green building saves or how many people pour through the doors of an eye-popping new museum. We are what we build. We build what we are. After a wild spree of overbuilding, and the shocks of disasters, wars, and economic collapse, the end of this tumultuous decade brought an opportunity to gaze back with keen-eyed clarity at the glories we left behind as well as our all-too-abundant failures. Amid the ugliness and the excess were gems that promised to light the way down a brighter path.

![]()

Copyright notice: The Introduction to Terror and Wonder: Architecture in a Tumultuous Age by Blair Kamin, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2010 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Blair Kamin

Terror and Wonder: Architecture in a Tumultuous Age

©2010, 304 pages, 70 halftones

Cloth $30.00 ISBN: 9780226423111

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Terror and Wonder.

See also:

- Our catalog of architecture titles

- Our catalog of Chicago titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog