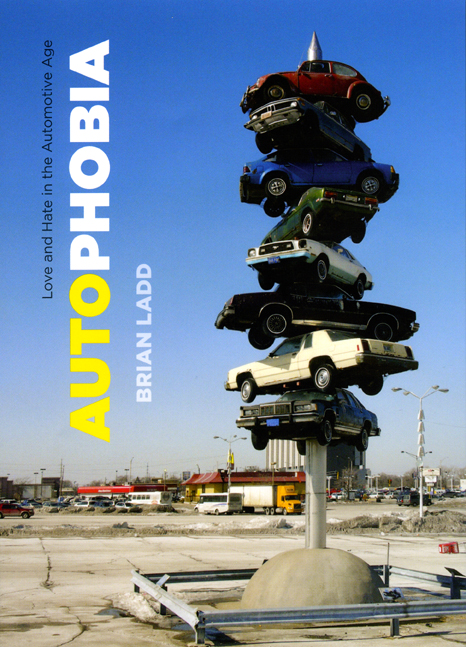

An excerpt from

Autophobia

Love and Hate in the Automotive Age

Brian Ladd

Roadkill: The New Machine Flattens Its Critics

“Roadkill” is the popular American term for the hundreds of millions of animals that fall victim to automobiles every year, their carcasses—large and small, furry or not (in the case of Texas armadillos)—littering the roads, glimpsed by speeding motorists but rarely eliciting even a wince, except when the beast in question is an aromatic skunk. In the American ideology of heedless progress, “roadkill” has also become a label for anything and anyone standing in the way of the relentless march of destiny. The fate of these obstructionists is unvarying: the speeding locomotive—or rather, the speeding car—of progress will flatten them. The automobile, our great vehicle of progress, demands its tribute, whether the hapless cats and deer on the road, the houses and neighborhoods swept away for new roads, or the shattered rural idylls. It is considered good form to dispatch all “roadkill” without any lingering sentimentality—although of course the human bodies crushed by speeding cars are generally granted a little more respect. We hope the grieving survivors of automotive casualties will appreciate the necessity of their sacrifice, and we certainly expect them to get over it.

Although the automobile’s conquest of public opinion has never been complete, it is astonishing how quickly cars became both fashionable and ubiquitous. The early motorists’ confidence was not misplaced. They knew the future was theirs, and the following century seems to have proved them right. But historians, like moralists, sometimes like to point out that might does not always make right. What if we look at the early history of the automobile from the roadkill’s point of view?

The Rising Menace

In many places the first motorcar appeared suddenly, roaring or clattering down the road and drawing hungry stares even as it shattered the peace forever. As a machine, however, the modern automobile emerged gradually, an amalgam of many technologies cobbled together to serve a variety of purposes. From the perspective of the automobile-centered late twentieth century, it was easy to believe that human beings had finally perfected the machine they had always desired. Although we have yet to discover any prehistoric cave paintings of cars, the thirteenth-century philosopher Roger Bacon is credited with predicting the possibility of them, and Renaissance drawings by Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht DÆrer depict what have been interpreted as prototype automobiles. Even as an actual machine, the self-propelled road vehicle has a long if slim history. In the decades after the invention of the steam engine in the eighteenth century, various French, British, and American entrepreneurs experimented with “road engines.” Innovation sputtered to a halt, however, after the rapid development of mobile steam engines riding on rails rather than roads. Not only did steam engines prove to be well suited to rails; the newly powerful railway interests pressed their advantage by demanding that restrictions be placed on their road-based rivals. The decisive phase of automotive development came much later in the nineteenth century, in the form of several technological breakthroughs shared among the industrialized nations of Europe and North America.

This innovation was driven less by the skill of inventors than by a growing demand for mobility—that is, a large base of potential customers. These were the prosperous middle classes of the industrial lands, far more numerous than any wealthy class ever before, and possessed of a desire and often a need to be mobile. Their appetite for travel had been whetted by transportation innovations of the previous decades, above all the railways. Since railroads usually operated on their own rights of way, they had not brought their speed to the existing network of country roads and city streets (until electric street railways appeared, just before automobiles did), nor could they satisfy a demand for small, maneuverable vehicles or for individual mobility. Numerous technologies competed to fill those needs: improved horse-drawn carriages; that new sensation, the remarkably efficient human-powered bicycle; and various motorized vehicles.

At the turn of the nineteenth century there were in fact three competing automotive technologies to choose from. Of the three, the gasoline-fueled internal-combustion engine gained a reputation as safer, faster, and more reliable, but that reputation was not entirely deserved, and it was by no means inevitable that both steam and electric automobiles would pass from the scene (or that the rival petroleum engine invented by Rudolf Diesel would be relegated to a secondary role). The invention of the internal-combustion automobile took place, like most inventions, in many steps, but is usually dated to the 1880s in southwestern Germany. The stationary four-stroke internal-combustion engine built by Nicolaus Otto in 1876 was installed in a carriage by his former assistants Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach in their workshop in Cannstatt, while, in Mannheim, Carl Benz modified a bicycle to create a three-wheeled, self-propelled vehicle. (Many of the early cars could accurately be described as “horseless carriages,” but others more resembled motorized bicycles.)

Popular histories of technology typically tell the stories of intrepid inventors whose clever machines changed the world by dint of their manifest usefulness or their inherent fascination. But no machine, no matter how clever, can conquer the world by itself. It needs promoters and enthusiasts. As it turned out, there was a vast market for automobiles as practical vehicles for transporting people and goods, but that market did not exist at the outset of the automobile age. The machines were too inefficient, unreliable, and expensive, and, more important, the established vectors of transportation had to be rearranged before the new machines could take control. Above all, this meant that roads—and ultimately cities—had to be rebuilt to accommodate the new vehicles. What bridged the gap between the invention and its practical, everyday use were the enthusiasts.

They appeared during the 1890s, especially in France, where the firm of Panhard & Levassor licensed Daimler’s engine. Paris and the French Riviera were the first places where cars became fashionable. (The French influence is apparent in the fact that many languages have adopted the French word “automobile,” not to mention “chauffeur” and “garage”—although speakers of other tongues stopped short of calling their motor fuel “essence.” In the early years, there also seems to have been less opposition to car use in France than in neighboring lands.) As the first cars wheezed down city streets, they drew crowds of the curious and the enthralled, and early auto races demonstrated the thrilling possibilities of road travel at breathtaking speeds—as fast as a train, but free of tracks, locomotives, and engineers. Wealthy and adventurous men (and a few women) in many lands began to acquire their own automobiles and to venture around town and across the countryside in them.

For the early enthusiasts, speed was the key attraction, coupled with the sense of individual mastery that came with driving. The railroad had long given people the chance to move across the earth at breathtaking speeds, but its path was restricted to its rails and its control to a professional engineer, with passengers confined to a passive role. Cars promised a different experience—not, for many years to come, a more comfortable journey, but rather a more exhilarating one. In the 1890s, when most people were no more likely to drive a car than to ride a racehorse, auto races promised thrills for a few drivers as well as crowds of onlookers. Crashes were common, often fatal, and part of the excitement of the race. The machine’s power—the power of life and death—depended on an individual driver, a role to which anyone could aspire. Soon the airplane would come along to offer some of the same thrills, but only for a select few, and not in the narrow confines of city streets or country lanes. The automobile, by contrast, let ordinary people (or at least ordinary people with money) take control of a speeding vehicle on familiar roads, with exciting and often disastrous results.

Speed was never the only reason to drive, of course, and in 1902 an automotive writer was confident that “in time the intoxication of the rapid motion of the automobile will wear off, and the pleasure of using such machines will be found in the opportunity that it gives to enjoy fresh air, change of scene and the beauties of nature, with the sense of freedom and independence that cannot be enjoyed in railroad trains.” Certainly some motorists came to prefer these gentler pursuits, but many others have shared the spirit of the thrill-seeking English writer Aldous Huxley (famous, ironically, for the dystopian Fordist future portrayed in his novel Brave New World), who was still insisting years later that the best modern intoxicant was “the drug of speed,” which “provides the one genuinely modern pleasure,” a feeling only available in a car going upwards of seventy miles per hour.

In the beginning the automobile was a toy, suitable for racing, thrills, and leisure outings. Perhaps someday it will again be mainly a toy, but for now, millions of people across the world have come to see it as a necessity of life. Although they may explain that necessity in terms of rationally defensible needs of daily life, many of them still rely on their cars to satisfy thoroughly irrational passions: for speed, thrills, and aggression, or for a sense of autonomy and individuality. For most of its users, a car is many things at once, and therefore not easily replaced.

In 1900 car owners were almost by definition wealthy, especially since they often employed chauffeurs: many wouldn’t have dreamed of trying to operate their own vehicles. Automobiles became the most visible intrusion of city life into the countryside—noisier, dirtier, and more dangerous variations on the bicycles that had been all the rage a few years before. When Edith Wharton exclaimed that “the motor-car has restored the romance of travel,” in 1908, she meant that her car and chauffeur could carry her to the most picturesque towns in France. In rural Europe, cars remained a sign of wealthy urban invaders into the 1930s. Farmers and villagers watched them roar (or splutter) by, get stuck, or run off the road, and they reacted with amusement, contempt, fear, hatred, envy, or perhaps admiration.

The emblematic English motorist was, curiously enough, an amphibian: the character of Mr. Toad in Kenneth Grahame’s popular 1908 children’s story, The Wind in the Willows, embodies the heedless, thrill-seeking, upper-class motorist, intoxicated by speed and completely helpless against his own irresistible urge to race and crash motorcars, until his reckless ways land him in prison. Still, Toad was ultimately a harmless and even lovable eccentric. The prolific English philosopher C. E. M. Joad could not bring himself to see real human motorists as anything less than mortal threats to all civilized refinement. In a 1927 book (whose subject was, significantly, the pernicious influence of everything American) he came straight to the point: “motoring is one of the most contemptible soul-destroying and devitalizing pursuits that the ill-fortune of misguided humanity has ever imposed upon its credulity.” The motorist was nothing but an obnoxious showoff: he “desires to advertise to the world at large that he has amassed enough money to hurl himself over its surface as often and as fast as it pleases him.”

It was usually the machines’ noise that announced their arrival in the countryside. Many early drivers, inspired by racers, wanted their vehicles to roar (much as many motorcyclists do today) and thereby made themselves very unpopular, at least until mufflers became obligatory. Joad likened the noise of cars sputtering down country roads to “a regiment of soldiers” who “had begun to suffer simultaneously from flatulence.” Motorists also liked to announce their presence (as if that were necessary) by blowing their horns in a cacophony like “a pack of fiends released from the nethermost pit.” The eminent German sociologist Werner Sombart complained bitterly of a world in which “one person was permitted to spoil thousands of walkers’ enjoyment of nature.” Joad raged at the “Babbits” who claimed they could enjoy the countryside while racing across it, filling it with fumes and an infernal din: “Everyone knows that the only way to see the country is to walk in it.” (Joad’s translation of good taste into groupthink—“everyone knows”—is all the more astonishing when, two pages later, he projects the same arrogance onto the motorist: “Like everyone of vulgar tastes, he thinks that all men share them.”)

In England and Germany, the heartlands of Romanticism, movements to protect the endangered countryside from the ravages of modernity had arisen before the automobile age, but it was in the decades after 1900 that they acquired a sense of urgency. As an English observer lamented in 1937, “the car, unlike the train, does not clot its horrors at the journey’s end but smears them along the way.” In the United States, where greater numbers of cars made the threat more acute, the wilderness-preservation movement was almost entirely a product of the automobile age, and its leaders’ paramount goal, during the 1930s in particular, was to cordon off pristine areas from the automobile. Vast and remote Yellowstone and Yosemite may have been very different places from the South Downs or the Black Forest, but in every case their defenders feared that the automobile would upset a precarious balance, bringing too many people, too quickly, and perhaps the wrong sort of people. The automobile’s critics scoffed at the claim that motorists had a right to bring their noisy vehicles with them. After all, as Joad observed, they gained nothing from the experience: “From the country they are completely cut off; they cannot see its sights, hear its sounds, smell its smells, or enjoy its silence.”

Joad was just as certain that motoring was bad for the motorist. “At the end of the journey he descends cold and irritable, with a sick headache born of rush and racks. He clamours for tea or dinner, but, lacking both bodily exercise and mental stimulus, he eats without appetite, and only continues to eat because at a motoring hotel there is nothing else to do. It is at such places that the modern fat man is made.” Some might think Joad was prescient here; but this is snobbery rather than analysis. Still, in his defense we might take note of the fatuous claims being made for the physical and psychic benefits of motoring. Many a car-loving physician praised the invigorating effects of swift movement through fresh air. New York City health commissioner Royal S. Copeland (later a U.S. senator) went further in 1922: “Most of us get enough exercise in the walking necessary, even to the most confined life, to keep the leg muscles fairly fit. It is from the waist upward that flabbiness usually sets in. The slight, but purposeful effort demanded in swinging the steering wheel, reacts exactly where we need it most. Frankly I believe that steering a motor car is actually better exercise than walking, because it does react on the parts of the body least used in the ordinary man’s routine existence.” The country walker Joad begged to differ: “Observe the bored and scowling couple lolling in this Daimler which is just about to drive you off the road into the ditch. The man is puny, and pot-bellied; the woman flabby, yellow and wrinkled. Their minds are vacant, their tempers irritable and their bodies idle and cold.” Soon the addition of quarreling children in the back seat would complete the picture of domestic automotive bliss.

No one claimed driving was healthy for pedestrians or bystanders. Apart from the danger to their lives and limbs, there was, first of all, the dust. Country dwellers wailed at the clouds of dust descending on their lungs, their homes, and their gardens. Unpaved country roads (that is, nearly all of them) had always been dusty, but the tires of speeding cars churned the dust faster and farther than horses, oxen, or wagons ever had. A statement from a 1909 British road-building handbook reveals the severity of the plague (if not necessarily an accurate diagnosis of it): “It is a matter of common knowledge that our great infantile mortality is largely attributable to dust.” The problem would eventually be solved by better road construction, and experiments with new pavements began early in the auto age. At first, however, it was hard to imagine that such expense could ever be justified, and discussion turned to speed limits and even to outright bans on automobiles.

As unpleasant as the newfangled machines themselves were, the atrocious behavior of their operators only began with horn honking. Unsuspecting farm dogs and fowl were slaughtered by the thousands as they wandered onto once-safe roads. Some drivers—perhaps not many, but enough to besmirch the reputation of all—made a sport of running them down. Many others simply couldn’t understand what all the fuss was about—coming, as they did, from a class that did not have to count its chickens. Looking back from the calmer atmosphere of the 1920s, a German motor club official evoked an era of rural hysteria: “Naturally things were not as bad as they were portrayed in the village newspapers. Whenever a world-weary hen darted under a car, the Podunk Times could be counted on to publish an outraged philippic under the headline ‘Automotive Mass Murder.’” It is hardly surprising that motorists chose the ridiculous chicken as the symbol of rural resistance. In 1913 the Paris newspaper Le Figaro recounted the legend of the “automotive chicken”: farmers, it was said, bred it especially for its ability to dash under the wheels of passing cars, thus enabling its owner to extract five francs in damages from the motorist. (American rubes allegedly played for higher stakes: Long Island farmers were rumored to steer their worn-out horses into the path of William K. Vanderbilt’s racing car, confident that the rich gentleman would pay handsomely for a slaughtered nag.)

Even as rural folk complained about their endangered fowl, they embraced the nobler horse as the symbol of their threatened way of life. On roads that had long belonged to horses, motor cars were a terror to the beasts and their drivers alike, with spooked animals causing their share of calamities. Motorists were not always sympathetic, blaming hostility on the envy and sloth of the unmotorized masses. Most motorists had next to nothing in common with impoverished cart drivers, who often had to spend every daylight hour on the road, snoozing while their animals picked their way along. Auto clubs and magazines buzzed with bitter complaints about the rural conservatism that reflexively took the side of the dumb horse (and its dim driver) against the clever motorist. In 1904, a German motor journal deplored the press’s reference to “automobile accidents” even when the automobile was not the cause: “The noble horse, despite all its virtues still stupider than a motorist, remains untouchable, although it has been proved a hundred times that horses and horse-drawn wagons cause more accidents that automobiles.” A similar lament appeared in an Italian auto magazine in 1912: “Horses, trams, trains can collide, smash, kill half the world, and nobody cares. But if an automobile leaves a scratch on an urchin who dances in front of it, or on a drunken carter who is driving without a light,” then woe to the motorist.

Nor did rural people adapt adroitly to the new dangers: with alarming frequency, speeding cars maimed and killed humans as well as chickens. Motorists fumed at the astonishing stubbornness of people who refused to recognize the new realities of the road: if pedestrians did not change their ways, they were to blame when calamity (in the form of a car) struck. As a contributor to a German motor magazine observed in 1909, more in sorrow than in anger, “A large proportion of accidents happen because the other users of the street refuse to acknowledge and adapt to the changed circumstances brought about by the appearance of the motor car. The heedlessness with which the public still crosses the busiest streets is beyond belief; and many parents let their children use the street as a playground, as if streetcars and automobiles simply don’t exist.” Still, only the most callous expected to be able to kill or maim passersby without consequences—probably not even Colonel J. T. C. Brabazon, a Conservative MP (and later minister of transport), who, outraged by a 1934 proposal to impose speed limits in order to save lives, sputtered, “Over six thousand people commit suicide every year, and nobody makes a fuss about that.” (This callousness has always remained just beneath the veneer of civility, surfacing at the end of the century in fantasy video games like Carmageddon, which rewards “drivers” for killing pedestrians.)

The first traffic deaths in any town or village were shocking incidents, but as early as 1906, Prince Heinrich zu Schnaich-Carolath noted on the floor of the German parliament that car accidents, often deadly ones, “have unfortunately become a regular column in the daily press.” As the Russian writer Ilya Ehrenburg declared portentously in 1929, “At first such things were known as ‘catastrophes.’ Now people speak of ‘accidents.’ Soon they’ll stop speaking altogether. Silently they’ll haul away the victim and silently write down the number. Sentimental neighbors wipe their noses, of course, and philosophically minded people argue about the ‘new peril.’ Commissions discuss protective laws. But the automobile keeps right on doing its job. . . . It only fulfills its destiny: It is destined to wipe out the world.”

Ehrenburg’s jaundiced view of the course of civilization was not widely shared. From the beginning, skeptics had to face the charge that they stood in the way of progress. As a German observer asked in 1906, “Who are these people who cry for government help against the motorists? They are the same ones who didn’t want gas lighting half a century ago and who petitioned the King of Prussia to stop the railroad being built from Berlin to Potsdam.” These “same people” think “the automobile is the personification of progress, and since they always fight that, they have to clamor against the petroleum-fueled monster.” The condemnation of car critics as enemies of progress has remained boosters’ trump card for a century, apparent, for example, whenever commentators sneer at proposals to curb auto use by invoking the Duke of Wellington’s apocryphal complaint that railroads would “only encourage the common people to move about needlessly.” The reactionary duke’s modern counterparts stand accused of wanting to return us to the unlamented “horse-and-buggy days.” Yet already in 1908 the French writer and motorist Octave Mirbeau savored the irony of these claims: “How frustrating, how thoroughly disheartening it is that these pig-headed, obstructive villagers, whose hens, dogs and sometimes children I mow down, fail to appreciate that I represent Progress and universal happiness. I intend to bring them these benefits in spite of themselves, even if they don’t live to enjoy them!”

It was easy to dismiss passionate car critics as conservatives, snobs, or defenders of privilege. From the beginning we can distinguish two strands of rural complaint, both with a conservative tinge: the poor peasant’s resentment of the highhanded rich motorist, and the outraged good taste of educated people who enjoyed their quiet sojourns in the countryside. They were horrified by the noisy machines and the crude behavior of their fellow visitors from the city: their reckless and sometimes deliberately dangerous driving, their condescension toward the rustics they encountered, or the litter they left behind for the country folk to clean up. What prosperous car critics shared with peasants was a revulsion at violence, boorishness, and ostentation and, at bottom, a perception of motorists as antisocial.

Taking Action

The articulate snobbery of Joad and Sombart should not blind us to the fact that cars were mainly toys of the well-to-do—at least briefly in the United States, for much longer in Europe, and still today in many lands—and a poor and carless majority has borne the brunt of what economists call the “negative externalities” of auto use. For example, by the 1920s rural English hospitals were staggering under the costs of treating auto accident victims—the motorists who careened off the roads as well as the locals who got in their way. Poor country folk grumbled but saw little recourse against people of more wealth and influence. It is harder to know what these poor people thought, since they were less likely to explain themselves in writing. What we do have is evidence of the actions some people took to defend roads they saw as theirs.

Stone throwing was common. There are many recorded examples from Germany and Switzerland, but things were worse in the Netherlands, according to a pioneering German woman motorist, who recorded in her diary in 1905 that “a journey by automobile through Holland is dangerous, since most of the rural population hates motorists fanatically. We even encountered older men, their faces contorted with anger, who, without any provocation, threw fist-sized stones at us.” The more typical culprits were boys, but the fact that their misbehavior was so common suggests that parents chose not to discourage their escapades. Angry young farmers sometimes deployed another readily available weapon: a bucket of fresh dung. Or they strewed nails and broken glass on roads. Between 1904 and 1906, farmers around Rochester, Minnesota, plowed up roads to prevent cars from passing. Farmers near Sacramento, California, dug ditches across roads in 1909 and actually trapped thirteen cars. Worse yet were ropes and wires tied between trees to block roads. If firmly attached, they could do great damage. A shocking case occurred in the Prussian countryside outside Berlin in 1913, when a wire strung across a highway by unknown assailants struck a couple speeding back to the city after a Sunday drive, beheading them.

Direct confrontations between motorists and angry peasants were common enough, as the American millionaire and motor enthusiast William K. Vanderbilt II could attest. Even as he personally popularized the automobile in some circles, he seems to have single-handedly provoked international hostility to it as well. He has been credited with enraging the local populace enough to inspire the first speed limits near his homes in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1900, and on Long Island in 1902. Nor did he have an easy time on his European motor tours. In Pau, France, in 1899, after he killed two dogs that were attacking his tires, he had to race away from an angry mob. A few years later, also in France, he fired warning shots after being threatened with whips and rocks. Faced with another irate mob after his car struck and injured a Tuscan child in 1906, he drew his revolver again, but several men seized it and proceeded to hit and kick him until police intervened. Three years later, it was Swiss farmers who beat him up and threatened to burn his car.

Even if motorists had reason to be fearful, they kept venturing into the countryside, often taking precautions to protect themselves. Both sides made regular use of whips. Recommendations that farmers be prepared to use their guns against cars made it into print in several midwestern U.S. states, while German motorists’ handbooks before World War I routinely advised drivers to carry weapons for their protection. Some motorists also thought it prudent to flee the scene of an accident, for fear of worse things being done to them by enraged peasants—who would of course be all the more incensed at the hit-and-run drivers’ arrogance. A 1909 German law even permitted drivers to abscond from the scene of an accident, as long as they reported to the police the next day. Still, it made for a bit of an uproar when, in 1910, a member of the German parliament from an anti-Semitic splinter party wrote a newspaper article blasting the “completely or half drunk” speeding road devils who threatened honest rural workers, and urging every wagon driver to get a revolver “so that you can defend yourself when the modern vermin attacks you.”

He was not the only rural politician who exploited anti-auto sentiments to rally his constituents against the rich urban interlopers. Nor is the anti-Semitic connection surprising, since it was common to blame Jews both for “nomadic” mobility and for urban influences, especially in central Europe. The stereotype could signal vicious prejudice but might also be dismissed with humor. Even a German motoring magazine joked that the answer to the question “Who was the first German motorist?” was “Jakob Israel from Berlin.” Politicians from mainstream parties often abhorred motorists, too. That became clear in a session of the Prussian parliament in 1908, in which Baron von Eynatten mocked a brochure published by the Imperial Automobile Club, an organization enthusiastically supported by the emperor himself. To laughter and applause from his colleagues, Eynatten read out lines from the brochure in a scornful tone—assertions, for example, that “panic on the part of the public” caused most accidents, that coachmen must be made to realize that “quiet times on country roads are a thing of the past,” and that “the road is for vehicles, not for pedestrians” to linger and make conversation. England, meanwhile, echoed with scorn for the “road hogs.” In a 1903 parliamentary debate, Sir Brampton Gurdon demanded an end to leniency: “I would almost consent in some cases to the punishment of flogging.”

Rarely, however, did this kind of rhetoric spur any political action, not even in Europe, where the era of rural opposition to automobiles lasted much longer than in the United States. There were, of course, economic interests at stake as well. Soon the auto industry and related services would become an economic force that few politicians dared to defy. At first, however, they felt the pressure of existing interests threatened by the automobile. We can, for example, detect the hand of the horse-and-cart lobby in a 1908 English poster that lamented the loss of 100,000 jobs in that industry only after capturing the attention of passersby with an attack on the “reckless motorists” who “kill your children,” dogs, and chickens, “fill your house with dust” as well as “spoil your clothes with dust” and “poison the air we breathe.”

The resort to weapons grew out of anger over real confrontations, but was also fueled by an inchoate fear of the other side. As long as motorists were strangers, and often rude ones, they represented the front rank of a frightening invasion of alien mores and technology. In 1903, a rural Michigan newspaper slyly played on its readers’ presumed equation of automobiles with uncivilized savagery: “A Crow chief has discarded the tomahawk for an automobile. The cunning old murderer!” Automobiles represent the more abstract threat of modern technology in Hermann Hesse’s cantankerous 1927 novel Steppenwolf, in which “the struggle between humans and machines” takes the form of a fantasy scene of snipers gleefully shooting down passing cars and drivers—a preview of later video games, perhaps, except that the latter invariably take the motorists’ side.

For a few years, some jurisdictions were willing to entertain the idea of banning cars. In the late 1890s, when the citizens of Mitchell, South Dakota, heard that someone in the state capital, Pierre, over a hundred miles away, had built a motor vehicle, they prohibited its use on their streets. Most such attempts to ban cars were short-lived or unenforced, gone by about 1905 in some West Virginia counties, for example. Even the exclusive New England island resorts of Mount Desert, Maine, and Nantucket, Massachusetts, relented within a few years. (The exception is Mackinac Island, Michigan—ironically, a traditional summer playground of Detroit’s elite—which has held to its ban for more than a century.) The sanctity of the Sunday stroll inspired Sunday driving bans in parts of Germany and Switzerland before and during World War I. The most notorious ban was imposed by the impoverished Swiss alpine canton of GraubÆnden, home of such famous resort towns as Davos and St. Moritz. Its total prohibition of cars began in 1900 and was repeatedly reaffirmed by popular referendums (albeit also granted some exceptions) until it was finally repealed in 1925. It was easy to caricature these mountain men (women could not vote) as dull-witted peasant reactionaries, but their resentment was grounded in the solidarity of villages hugging narrow mountain roads and in cold calculations of the costs of road maintenance, the viability of their newly completed mountain railway, and even the preference of spa owners for the more reliable paying visitors who arrived by train and who came expressly to enjoy the peace and quiet now threatened by automobiles.

Meanwhile, severe restrictions that amounted to a virtual ban were disappearing. Fearing that mobile steam engines might explode, the British parliament passed the notorious Red Flag law in 1865. Until motorists got it repealed in 1896, it limited the speed of a “road locomotive” to two miles per hour in town and four in the country, and required that it be preceded by a man on foot carrying a red flag to warn passersby. The state of Vermont kept a similar law for several more years; Iowa tried one that required motorists to telephone ahead to warn towns of their arrival.

Hardly anyone outside of the Alps defended this kind of restriction much after 1900. In its place came more or less moderate speed limits set by local or national governments from the 1890s on, much disputed and frequently changed thereafter. The limit in town was typically equated to that of a trotting horse, about ten miles per hour, with rural limits varying much more widely if they existed at all. Even where the rules were clear, their enforcement furnished plenty of tinder for conflict. From the very first years of the twentieth century, drivers in many lands bewailed the small-town speed trap. Police sometimes strung ropes across the road to stop scofflaws. In Chicago’s North Shore suburbs, they soon switched to wire cables, since, as a motor magazine reported, “the more determined offenders . . . fitted scythelike cutters in front of their machines” to cut the ropes. Auto clubs in Britain and the U.S. organized patrols and signals to warn their members of speed traps. In the 1920s, while a German magazine maintained a list of offending localities, French auto clubs called for a boycott of “autophobic” towns, and the strict enforcement of speed limits prompted a British motor magazine to do the same in 1935. The clubs also thought they should be given all responsibility for disciplining the few bad apples in their midst, although they made few moves to do so. Nor, for that matter, did many courts hand down severe penalties for traffic violations, in part because judges often saw motorists as respectable citizens from their own social circles. In some places, motorists had more to fear from vigilante anti-speeding groups. But they have never ceased to resent speed traps, which reveal all too crassly the arbitrary limits of the independence and self-control on which drivers pride themselves.

Even if the small-town speed trap remained a sore point, in the U.S. the fundamental urban-rural tension dissipated by the 1910s, as the Ford Motor Company led the way in producing cars cheap enough for the masses. In a 1906 speech, Woodrow Wilson, then the president of Princeton University, put forth the critics’ standard view, arguing that “nothing has spread socialistic feeling in this country more than the use of automobiles. To the countryman they are a picture of arrogance of wealth with all its independence and carelessness.” Wilson’s view was more typical of Europe than of America, and in later years, his words have frequently been mocked as evidence of the fatuousness of car critics. Even at the time, before Ford’s Model T, American automobile proponents argued that he was out of touch with the contemporary countryside. Soon, the roar of an approaching car no longer meant the arrival of strangers, since the Model T became an affordable and nearly indispensable tool of rural life. Even urban visitors were often welcomed for the dollars they brought. Things remained very different in most other places, although Canada and Australia, other prosperous and spacious lands dotted with isolated farms, began to follow the American lead. In Europe, only a few favored places attracted enough motoring tourists to boost the local economy, and up to the middle of the century few farmers could afford their own automobiles. By 1929, the U.S. had more than twenty motor vehicles for every hundred people, an average of nearly one per family (although a large minority of families had none). New Zealand, Australia, and Canada had about half as many. Britain and France led Europe with about four or five cars per hundred people.

![]()

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 14–28 of Autophobia: Love and Hate in the Automotive Age by Brian Ladd, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2008 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Brian Ladd

Autophobia: Love and Hate in the Automotive Age

©2008, 204 pages, 20 halftones

Cloth $22.50 ISBN: 9780226467412

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Autophobia.

See also:

- Our catalog of history titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog