< previous part | next part >

The Community of Commerce

The new global economic system ties Northwesterners to an unlikely group of international partners

Muslim cleric Mohamad Joban never expected, when he trained in Egypt, to help speed the international flow of french fries.

But the global economy assembles a diverse cast of characters.

One snowy day last January, Joban emerged from an 18-seat Metroliner plane in Pendleton and adjusted his white kufi, a skull cap, against the frigid breeze. He stepped onto the windswept airstrip, an exotic figure in his thobe, a flowing robe worn by Muslims.

“They took me in a special plane from Sea-Tac,” said Joban, an Indonesian who spends most of his time counseling prisoners near Olympia. “They showed me how to proceed.”

Joban had never toured a french fry factory, but he knew his mission. He would examine the J.R. Simplot Co.’s plant in Hermiston to see whether it deserved the coveted Halal certification needed for exporting food to Muslim countries, including Indonesia.

A Halal stamp would become another strand in a growing web binding the Northwest to the world. The economic web, spun largely during the region’s export and investment boom in the early 1990s, remained all but invisible until Asia’s catastrophes brought it suddenly into view.

A month after Jobans visit, the Simplot plant would process a batch of potatoes grown by Hutterite farmers in Eastern Washington and bound for Indonesia. By January, the tubers grown in Circle 6, one of the sect’s irrigated circular fields, were piled 20 feet deep in a climate-controlled warehouse longer than a football field. A young man from the Hutterite colony checked on the potatoes, alive and emitting heat, each day.

Lola DuPuis, a 20-year worker for the J.R. Simplot Co. in Hermiston, culls defective french fries from a batch bound for Indonesia. A Muslim cleric inspected the plant to ensure that fries were processed according to religious standards.

The task of preparing McDonald’s fries involves a remarkably broad spectrum of cultures, religions and traditions, considering the unfailing uniformity of the fries themselves. By the time these spuds were done, they would have been grown by members of a Germanic sect, sanctified by Muslims, transported by Protestants and consumed by Jews and Chinese converted to Catholicism in Asia.

All of those along the french fry chain participated while retaining their beliefs and traditions. But each would be changed by links to the global economy.

Northwest businesses had to become more sensitive to Asian cultures as exports soared during the past decade. Millworkers who once cut 2-by-4s converted to saw traditional Japanese posts and beams. Farmers who once manhandled fruit crates learned to pamper individual apples for exacting customers in Asia.

Simplot managers wanted the nod from Joban to boost their exports from Hermiston, which already exceeded 220 million pounds a year. A Halal certificate, much like the Jewish kosher designation, would assure Islamic customers that Simplot prepared fries according to strict Muslim tenets.

“The problem is that when a product comes from a Western country,” Joban said, “most Muslims doubt that it’s Halal.”

* * *

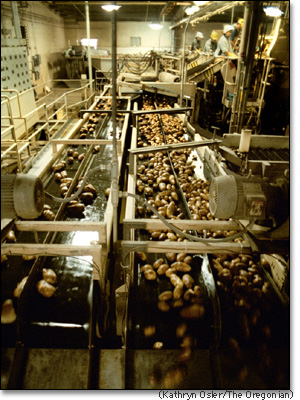

Workers at the J. R. Simplot Co. plant in Hermiston cut blemishes from washed potatoes. The plant, which employs 650 people, is one of many Northwest plants targeting Asian markets.

Potato patriarch J.R. Simplot, who founded the company that bears his name, built the mammoth Hermiston plant for $15 million in 1977. The factory, designed specifically to produce McDonald’s french fries, is one of 11 fry plants in the Columbia Basin owned by big food-processing firms.

Exports from Hermiston grew so fast that in 1990, Simplot launched a barge on the Columbia River to carry what growers and processors call “Mac fries” to Portland. He named the vessel Esther L., after his wife. In a blind taste test that year, McDonald’s’ chose Hermiston fries as the world’s best, a model for all other plants.

Simplot’s company, which makes more Mac fries than any other producer, sends 4 million pounds of frozen french fries to Asia each week. The company commands between 30 percent and 40 percent of the international fry business.

Simplot himself usually refuses to wear the hair net required for visitors to the Hermiston plant, which runs 24 hours and employs 650 people. But Joban politely accepted one.

He inserted orange ear plugs. He walked onto a vibrating catwalk above a hissing vat of potatoes.

The factory is a torture chamber for spuds. Scalding steam explodes brown skins. Workers with stubby knives gouge out black spots.

High-pressure water blasts potatoes at 35 mph through a pipe into brass blades arranged in a quarter-inch grid.

Laser-guided knives whack imperfections from the raw shoestring fries. The fries cook in a blancher and dry in a dryer. They partially fry at 380 degrees, flash-freeze at 75 degrees below zero and shake on a stainless-steel screen.

Mechanical jaws grab the fries and drop them into brown paper bags. Machines squish the bags to remove excess air and pass them through a metal detector.

Correctly processed, an extra-long fancy fry will be soft inside from boiling and crisp outside from baking and frying. It will have an audible crunch without tasting dry. Unless it happened to come from a potato’s watery core, it will stand erect in a cardboard packet.

Industry veterans say they can taste whether a fry came from a potato grown in the Columbia Basin, Idaho’s Treasure Valley or North Dakota’s Red River Valley.

The Hermiston plant’s success in penetrating Asian markets came as Northwest exports soared, leading national growth. Between 1990 and 1997, annual shipments abroad from Oregon blasted off, doubling and exceeding $10 billion a year.

The export take-off, coming atop the Northwest’s rapid high-technology development, helped diversify a regional economy that once depended on timber, fish and unprocessed farm products. The point of the game was to add value to goods—selling milled lumber, for example, instead of raw logs—to create better-paying jobs at home.

French fries worked just this way. Simplot bought raw potatoes for about a nickel a pound. As fries, they were worth 30 cents a pound by the time they reached Northwest ports. The difference went to U.S. salaries and corporate revenues, rippling through the economy at cash registers across the Northwest.

Food processing is a potent economic force. Hire 1,000 workers for a new potato-processing plant in Washington state, and about 3,250 new jobs will result in other industries ranging from construction to restaurants.

In 1991, Washington’s food-processing industry surged past lumber and wood products and became the state’s second-largest manufacturing employer, behind transportation equipment. Food processors added $2.45 billion to Washington’s $4.38 billion of agricultural production that year.

Northwest companies that didn’t plan to go international often were forced into it. Columbia Basin farmers once supplied 40 percent of U.S. french fries. But in 1996, Canadian fry producers more than doubled their production. They flooded the U.S. market with fries sold at attractive prices for weak Canadian dollars.

The Simplot factory is a torture chamber for spuds, which hit knives at 35 mph and become french fries. Once a month, workers clean the plant and switch to vegetarian oil to make Halal fries for Muslim customers in Asia.

The Canadian influx pushed Simplot to close one of two inefficient french fry factories in a Caldwell, Idaho, complex, where 340 people lost their jobs, and a plant in Grand Rapids, Mich. The company halved production in Heyburn, Idaho, laying off 377 people.

More than ever, Simplot counted on Hermiston, its main pipeline to Asia. Other Northwest spud processors also shifted to aim their fries at Asia as American chains expanded.

Customers flocked to T.G.I. Fridays in Taipei, the Hard Rock Cafe in Tokyo and McDonald’s outlets throughout the Far East. From 1993 to 1997, sales of U.S. frozen potatoes in the Far East nearly doubled to $265 million.

Fries were so popular that they muscled into unlikely places. In Thailand, even Pizza Hut served them.

The Northwest export boom went bust in late 1997 as Asian customers, battered by falling currencies and tight credit, slowed orders. Japan, Oregons biggest foreign customer, cut purchases by almost a quarter at one point, causing some of the first layoffs in the state due to Asias woes.

But McDonald’s, the Hermiston potato plant’s main customer, managed to increase its market share in Japan’s cutthroat fast-food market. So the factory continued at full throttle, even as Southeast Asian shipments faltered.

As Imam Joban moved through the plant, he learned that workers cleaned it thoroughly once a month. They unlocked padlocks on special pipes that substituted vegetarian soybean oil for the usual beef-based oil, a switch essential to Halal certification. Muslims can eat certain kinds of meat, but only if a devout Muslim slaughters the animal.

Veteran workers could tell by the distinctive vegetable-oil aroma when the plant was producing Halal fries for export to Indonesia and Singapore.

Joban approved the Halal certification, to the delight of Simplot managers. “I observed everything in the plant,” he said, “even the small, small things.”

But as Joban visited the Hermiston plant, his home country, Indonesia, descended into panic.

* * *

French fries took center stage in a bit of bizarre theater on Jan. 12 in Jakarta. Indonesia’s finance minister, eager to stop the rupiah’s six- month slide, faced a crush of television cameras in Jakarta with a red-and-white sign that said: “I love the rupiah.”

Prominent business tycoons, some in dark suits and others in batik shirts, pulled sheaves of $100 bills from their wallets, exchanging them for rupiah. Among them was Bambang Rachmadi, head of McDonald’s restaurant franchises in Indonesia. He changed $30,000 into rupiah.

Rachmadi said his outlets were deleting french fries from Value Meals because the imported potatoes had to be bought in dollars. The patriotic gesture caused consternation at Simplot headquarters.

A formal color photo of Rachmadi and his wife graces the interior of every McDonald’s in Indonesia. But the man who makes sure the fries arrive on time is Angus Karoll, a 27-year-old Australian who first saw J.R. Simplot profiled on Australia’s “60 Minutes” television show.

Karoll thought Simplot was the coolest guy in the world. He sent him a detailed proposal for distributing french fries throughout Indonesia, a sprawling country of about 17,000 islands.

Company officials put the young man in charge of warehouses spanning a distance equivalent to that between Portland and Boston.

Karoll found himself hiring a staff of 50, refilling warehouse coolant at midnight, answering 2 a.m. phone calls from Boise and cajoling barge captains to carry french fries to far-flung islands.

The business took off with the rise of fast food. Indonesia’s upwardly mobile population attracted Kentucky Fried Chicken, California Fried Chicken, A&W, Churchs and Wendy’s.

McDonald’s had opened 100 outlets by last year and planned to double that this year. Instead, when the rupiah plunged, Rachmadi closed 15 outlets.

Karoll struggled to cut expenses as the warehouse power bill jumped 30 percent because of climbing fuel prices. He flew back and forth to Boise, ensuring that the home office remained committed.

Most Indonesians cared more about food staples. As prices soared, customers lined up 20 deep at cash registers to buy sugar, rice and cooking oil before yet another increase.

The International Monetary Fund, the world’s economic emergency-room doctor, had already launched a $23 billion bailout for Indonesia.

The IMF wrote its standard prescription. It lent money on the condition that Suharto’s administration cut government spending and raise interest rates. The theory was that high rates would attract capital to Indonesia and slow the money flowing out, shoring up the rupiah. High rates and tight credit would also slow domestic spending, reducing imports and boosting exports. Ultimately, the theory went, the rupiah would steady, and interest rates would come down.

But Suharto balked, fearing social unrest and damage to family businesses. His resistance sapped confidence at a critical moment, spooking currency dealers, who worried that the IMF would back out.

They sold off rupiahs, forcing up prices. Indonesian stocks fell as investors doubted that companies would be able to pay off their foreign-currency debts.

McDonald’s sales tumbled. One restaurant advertised an “IMF packet,” just the basics: iced lemon tea, Filet-O-Fish, no fries.

The IMF, for trying to help, became the object of derision in much of Southeast Asia. Nationalistic critics claimed the West was seizing the chance to mold Asia in its image.

Lamenting the Westernization of Asia was nothing new. McDonald’s became a ready symbol for critics as the chain swept Asia. Nutritionists blamed fast food for increasing flab in Japanese as they switched from a diet based on rice and fish.

Some social commentators depicted Westernization as a new form of cultural imperialism. Some predicted the emergence of a homogenous, global culture that would wipe out local distinctions.

But although McDonald’s might have helped Westernize Asia, Asia also transformed McDonald’s.

Asian customers converted McDonald’s outlets into leisure centers, after-school clubs and meeting halls. McDonald’s franchisees invented the soy-flavored Teriyaki McBurger in Japan, the McSpaghetti in the Philippines, the chili-basil pork burger in Thailand and the mutton-based Maharaja Mac in India.

Harvard anthropologist James Watson chronicled the transformations in a 1997 report, “Golden Arches East.”

The main menu item that never changed, Watson found, was the french fry.

* * *

On Feb. 24, 1998, a month after Mohamad Joban certified the Hermiston potato plant, the tubers from Hutterite Circle 6 arrived at the scrubbed-down factory.

The potatoes rumbled along a portable red conveyer belt made by Spudnik Equipment Co., an Idaho company founded in 1958 after the Soviet Union launched the Sputnik satellite.

The spuds joined more from a handful of other farmers. About 60 tractor-trailer loads of tubers arrive at the plant each day. Farmers, who negotiate contracts with processors long before planting, don’t usually get paid until a month or so after delivery.

The Hutterite potatoes shot through the pipe and became Mac fries.

Lola DuPuis, a swing-shift worker at the plant, gazed at the relentless river of raw fries. She knew next to nothing of the Asian crisis, whose ripple effects were depressing company earnings around the world. That day, Nike Inc. confirmed that it would lay off hundreds of workers as Asian retailers bought fewer shoes.

But after 20 years at the plant, DuPuis knew french fries. She tended them five days a week from 4 p.m. to midnight, earning $8.41 an hour. She ate them at the McDonald’s outlet in town. And she bought them at the company store to keep frozen at home.

DuPuis spotted a piece of wire in the mix and grabbed it. Relieved at first, she felt a flash of irritation. Once, a green rubber glove made it all the way to Japan. A foreign object is anathema in a process geared for perfection.

Processors strive to make 40 percent of their A-grade fries more than 3 inches long to meet exacting industry standards. To satisfy McDonald’s, another 40 percent of the fries must be more than 2 inches.

The entire process on Line 4, from fresh Circle-6 Hutterite spuds to frozen fries, took 45 minutes. Boxed and shrink-wrapped, the fries waited in Simplots’ refrigerated warehouse, ready for export to Indonesia. Next, the fries would enter a chain of freight-forwarders, bankers, truckers, longshoremen, shippers, agents, importers and franchisees.

But the climate for shipments had drastically changed in the months since the potatoes were planted.

Exports of Oregon agricultural goods in 1997 dropped 14 percent from the year before, after years of steady increases. The Columbia-Snake Customs District, remarkable nationally for its longtime trade surplus, logged a $1.1 billion deficit.

Foreign investors pulled out, too, reducing the flow of capital that courses through the global economy.

One of the first casualties was a planned factory in Boardman that would have converted rejected french fries into ethanol. The ethanol would have been shipped to South Korea to make soju, a potent traditional drink.

South Korean distillers, strapped by the currency crisis, escalating debts and government restrictions on foreign investment, backed out as lead investors in the proposed $34 million plant.

In the spring of 1998, Northwest companies ranging from Mentor Graphics to Louisiana Pacific blamed Asia for lower earnings. Nike went on to lay off 1,600 workers, mainly because of Asias turmoil.

For the Northwest and the nation, it was just the start of the fallout from Asia.

< previous part | next part >