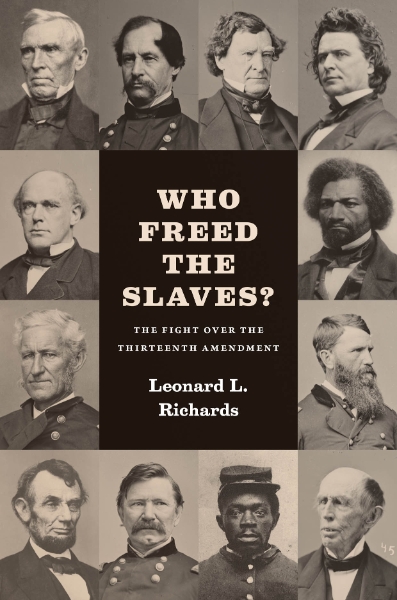

“This study of the political drive toward the complete abolition of slavery is most welcome. Leonard Richards has rescued from obscurity James Ashley, who managed the course of the Thirteenth Amendment through the House of Representatives. The reader will come away with greater appreciation for the courage and skill of those antislavery leaders who never gave up and eventually triumphed.”– James M. McPherson, author of Battle Cry of Freedom

Buy this book: Who Freed the Slaves?

Prologue

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 15, 1864

James Ashley never forgot the moment. After hours of debate, Schuyler Colfax, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, had finally gaveled the 159 House members to take their seats and get ready to vote.

Most of the members were waving a fan of some sort, but none of the fans did much good. Heat and humidity had turned the nation’s capitol into a sauna. Equally bad was the stench that emanated from Washington’s back alleys, nearby swamps, and the twenty-one hospitals in and about the city, which now housed over twenty thousand wounded and dying soldiers. Worse yet was the news from the front lines. According to some reports, the Union army had lost seven thousand men in less than thirty minutes at Cold Harbor. The commanding general, Ulysses S. Grant, had been deemed a “fumbling butcher.”

Nearly everyone around Ashley was impatient, cranky, and miserable. But Ashley was especially downcast. It was his job to get Senate Joint Resolution Number 16, a constitutional amendment to outlaw slavery in the United States, through the House of Representatives, and he didn’t have the votes.

The need for the amendment was obvious. Of the nation’s four million slaves at the outset of the war, no more than five hundred thousand were now free, and, to his disgust, many white Americans intended to have them reenslaved once the war was over. The Supreme Court, moreover, was still in the hands of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney and other staunch proponents of property rights in slaves and state’s rights. If they ever got the chance, they seemed certain not only to strike down much of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation but also to hold that under the Constitution only the states where slavery existed had the legal power to outlaw it.

Six months earlier, in December 1863, when Ashley and his fellow Republicans had proposed the amendment, he had been more upbeat. He knew that getting the House to abolish slavery, which in his mind was the root cause of the war, was not going to be easy. It required a two-thirds vote. But he had thought that Republicans in both the Senate and the House might somehow muster the necessary two-thirds majority. No longer did they have to worry about the united opposition of fifteen slave states. Eleven of the fifteen were out of the Union, including South Carolina and Mississippi, the two with the highest percentage of slaves, and Virginia, the one with the largest House delegation. In addition, the war was in its thirty-third month. Hundreds of thousands of Northern men had been killed on the battlefield. The one-day bloodbath at Antietam was now etched into the memory of every one of his Toledo constituents as well as every member of Congress. So, too, was the three-day battle at Gettysburg.

If Republicans held firm, all they needed to push the amendment through the House was a handful of votes from their opponents, either from the border slave state representatives who had remained in the Union or from free state Democrats. It was his job to get those votes. He was the bill’s floor manager.

Back in December, Ashley had been the first House member to propose such an amendment. Although few of his colleagues realized it, he had been toying with the idea for nearly a decade. He had made a similar proposal in September 1856, when it didn’t have a chance of passing.

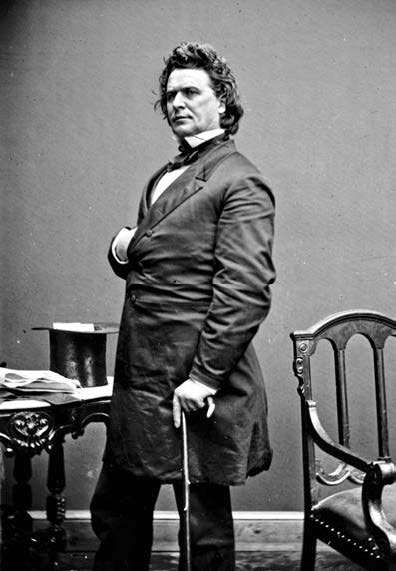

He was a political novice at the time, just twenty-nine years old, and known mainly for being big and burly, six feet tall and starting to spread around the middle, with a wild mane of curly hair and a loud, resonating voice. He had just gotten established in Toledo politics. He had moved there three years earlier from the town of Portsmouth, in southern Ohio, largely because he had just gotten married and was in deep trouble for helping slaves flee across the Ohio River. He was not yet a Congressman. Nor was he running for office. He was just campaigning for the Republican Party’s first presidential candidate, John C. Frémont, and Richard Mott, a House member who was up for reelection. In doing so, he gave a stump speech at a grove near Montpelier, Ohio.

James M. Ashley, congressman from Ohio. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection, Library of Congress (lC-Bh824-5303).

The speech lasted two hours. In most respects, it was a typical Republican stump speech. It was mainly a collection of stories, many from his youth, living and working along the Ohio River. Running through it were several themes that tied the stories together and foreshadowed the rest of his career. In touting the two candidates, he blamed the nation’s troubles on a conspiracy of slaveholders and Northern men with Southern principles, or as he called them “slave barons” and “doughfaces.” These men, he claimed, had deliberately misconstrued the Bible, misinterpreted the Constitution, and gained complete control of the federal government. “For nearly half a century,” he told his listeners, some two hundred thousand slave barons had “ruled the nation, morally and politically, including a majority of the Northern States, with a rod of iron.” And before “the advancing march of these slave barons,” the “great body of Northern public men” had “bowed down . . . with their hands on their mouths and mouths in the dust, with an abasement as servile as that of a vanquished, spiritless people, before their conquerors.”

Across the North, many Republican spokesmen were saying much the same thing. What made Ashley’s speech unusual was that he made no attempt to hide his radicalism. He made it clear to the crowd at Montpelier that he would do almost anything to destroy slavery and the men who profited from it. He had learned to hate slavery and the slave barons during his boyhood, traveling with his father, a Campbellite preacher, through Kentucky and western Virginia, and later working as a cabin boy on the Ohio River. Never would he forget how traumatized he had been as a nine-year-old seeing for the first time slaves in chains being driven down a road to the Deep South, whipping posts on which black men had been beaten, and boys his own age being sold away from their mothers. Nor would he ever forget the white man who wouldn’t let his cattle drink from a stream in which his father was baptizing slaves. How, he had wondered, could his father still justify slavery? Certainly, it didn’t square with the teachings of Christ or what his mother was teaching him back home.

Ashley also made it clear to the crowd at Montpelier that he had violated the Fugitive Slave Law more times than he could count. He had actually begun helping slaves flee bondage in 1839, when he was just fifteen years old, and he had continued doing so after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made the penalties much stiffer. To avoid prosecution, he and his wife had fled southern Ohio in 1851. Would he now mend his ways? “Never!” he told his audience. The law was a gross violation of the teachings of Christ, and for that reason he had never obeyed it and with “God’s help . . . never shall.”

What, then, should his listeners do? The first step was to join him in supporting John C. Frémont for president and Richard Mott for another term in Congress. Another was to join him in never obeying the “infamous fugitive-slave law”—the most “unholy” of the laws that these slave barons and their Northern sycophants had passed. And perhaps still another, he suggested, was to join him in pushing for a constitutional amendment outlawing “the crime of American slavery” if that should become “necessary.”

The last suggestion, in 1856, was clearly fanciful. Nearly half the states were slave states. Thus getting two-thirds of the House, much less two-thirds of the Senate, to support an amendment outlawing slavery was next to impossible. Ashley knew that. Perhaps some in his audience, especially those who cheered the loudest, thought otherwise. But not Ashley. Although still a political neophyte, he knew the rules of the game. He was also good with numbers, always had been, and always would be. Nonetheless, he told his audience to put it on their “to do” list.

Five years later, in December 1861, Ashley added to the list. By then he was no longer a political neophyte. He had been twice elected to Congress. Eleven states had seceded from the Union, and the Civil War was in its eighth month. As chairman of the House Committee on Territories, he proposed that the eleven states no longer be treated as states. Instead they should be treated as “territories” under the control of Congress, and Congress should impose on them certain conditions before they were allowed to regain statehood. More specifically, Congress should abolish slavery in these territories, confiscate all rebel lands, distribute the confiscated lands in plots of 160 acres or fewer to loyal citizens of any color, disfranchise the rebel leaders, and establish new governments with universal adult male suffrage. Did that mean, asked one skeptic, that black men were to receive land? And the right to vote? Yes, it did. And if such measures were enacted, said Ashley, he felt certain that the slave barons would be forever stripped of their power.

Ashley’s goal was clear. The 1850 census, from which Ashley and most Republicans drew their numbers, had indicated that just a few Southern families had the lion’s share of the South’s wealth. Especially potent were the truly big slaveholders—families with over one hundred slaves. There were 105 such family heads in Virginia, 181 in Georgia, 279 in Mississippi, 312 in Alabama, 363 in South Carolina, and 460 in Louisiana. With respect to landholdings, there were 371 family heads in Louisiana with more than one thousand acres, 481 in Mississippi, 482 in South Carolina, 641 in Virginia, 696 in Alabama, and 902 in Georgia.

In Ashley’s view, virtually all these wealth holders were rebels, and the Congress should go after all their assets. Strip them of their slaves. Strip them of their land. Strip them of their right to hold office. Halfhearted measures, he contended, would lead only to half-hearted results. Taking away a slave baron’s slaves undoubtedly would hobble him, but it wouldn’t destroy him. With his vast landholdings, he would soon be back in power. And with the right to hold office, he would not only have economic power but also political power. And with the end of the three-fifths clause, the clause in the Constitution that counted slaves as only three-fifths of a free person when it came to tabulating seats in Congress and electoral votes, the South would have more power than ever before.

When Ashley made this proposal in December 1861, everyone on his committee told him it was much too radical ever to get through Congress. He knew that. But he also knew that there were men in Congress who agreed with him, including four of the seven men on his committee, several dozen in the House, maybe a half-dozen in the Senate, and even some notables such as Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Senator Ben Wade of Ohio.

The trouble was the opposition. It was formidable. Not only did it include the “Peace” Democrats, men who seemingly wanted peace at any price, men whom Ashley regarded as traitors, but also “War” Democrats, men such as General George McClellan, General Don Carlos Buell, and General Henry Halleck, men who were leading the nation’s troops. Also certain to oppose him were the border state Unionists, especially the Kentuckians, and most important of all, Abraham Lincoln. Against such opposition, all Ashley and the other radicals could do was push, prod, and hope to get maybe a piece or two of the total package enacted.

Two years later, in December 1863, Ashley thought it was indeed “necessary” to strike a deathblow against slavery. He also thought it was possible to get a few pieces of his 1861 package into law. So, just after the House opened for its winter session, he introduced two measures. One was a reconstruction bill that followed, at least at first glance, what Lincoln had called for in his annual message. Like Lincoln, Ashley proposed that a seceded state be let back into the Union when only 10 percent of its 1860 voters took an oath of loyalty.

Had he suddenly become a moderate? A conservative? Not quite. To Lincoln’s famous 10 percent plan, Ashley added two provisions. One would take away the right to vote and to hold office from all those who had fought against the Union or held an office in a rebel state. That was a significant chunk of the population. The other would give the right to vote to all adult black males. That was even a bigger chunk of the population, especially in South Carolina and Mississippi.

The other measure that Ashley proposed that December was the constitutional amendment that outlawed slavery. A few days later, Representative James F. Wilson of Iowa made a similar proposal. The wording differed, but the intent was the same. The Constitution had to be amended, contended Wilson, not only to eradicate slavery but also to stop slaveholders and their supporters from launching a program of reenslavement once the war was over. Then, several weeks later, Senator John Henderson of Missouri and Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts introduced similar amendments. Sumner’s was the more radical. The Massachusetts senator not only wanted to end slavery. He also wanted to end racial inequality.

The Senate Judiciary Committee then took charge. They ignored Sumner’s cry for racial justice and worked out the bill’s final language. The wording was clear and simple: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

On April 8, 1864, the committee’s wording came before the Senate for a final vote. Although a few empty seats could be found in the men’s gallery, the women’s gallery was packed, mainly by church women who had organized a massive petition drive calling on Congress to abolish slavery. Congress for the most part had ignored their hard work. But to the women’s delight, thirty-eight senators now voted for the amendment, six against, giving the proposed amendment eight votes more than what was needed to meet the two-thirds requirement.

All thirty Republicans in attendance voted aye. The no votes came from two free state Democrats, Thomas A. Hendricks of Indiana and James McDougall of California, and four slave state senators: Garrett Davis and Lazarus W. Powell of Kentucky and George R. Riddle and Willard Saulsbury of Delaware. Especially irate was Saulsbury. A strong proponent of reenslavement, he made sure that the women knew that he regarded them with contempt. In a booming voice, he told them on leaving the Senate floor that all was lost and that there was no longer any chance of ever restoring the eleven Confederate states to the Union.

Now, nine weeks later, the measure was before the House. And its floor manager, James Ashley, expected the worst. He kept a close count. And, as the members voted, he realized that he was well short of the required two-thirds. Of the eighty Republicans who were in attendance, seventy-nine eventually cast aye votes and one abstained. Of the seventeen slave state representatives in attendance, eleven voted aye and six nay. But of the sixty-two free state Democrats, only four voted for the amendment while fifty-eight voted nay. As a result, the final vote was going to be ninety-four to sixty-four. That was eleven shy of the necessary two-thirds majority.

The outcome was even worse than Ashley had anticipated. “Educated in the political school of Jefferson,” he later recalled, “I was absolutely amazed at the solid Democratic vote against the amendment on the 15th of June. To me it looked as if the golden hour had come, when the Democratic party could, without apology, and without regret, emancipate itself from the fatal dogmas of Calhoun, and reaffirm the doctrines of Jefferson. It had always seemed to me that the great men in the Democratic party had shown a broader spirit in favor of human liberty than their political opponents, and until the domination of Mr. Calhoun and his States-rights disciples, this was undoubtedly true.”

Despite the solid Democratic vote against the resolution, there was still one way that Ashley could save the amendment from certain congressional death. And that was to take advantage of a House rule that allowed a member to bring a defeated measure up for reconsideration if he intended to change his vote. To make use of this rule, however, Ashley had to change his vote before the clerk announced the final tally. He had voted aye along with his fellow Republicans. He now had to get into the “no” column. That he did. The final vote thus became ninety-three to sixty-five.

Two weeks later, Representative William Steele Holman, Democrat of Indiana, asked Ashley when he planned to call for reconsideration. Ashley told him not now but maybe after the next election. The trick, he said, was to find enough men in Holman’s party who were “naturally inclined to favor the amendment, and strong enough to meet and repel the fierce partisan attack which were certain to be made upon them.”

Holman, Ashley knew, would not be one of them. Although the Indiana Democrat had once been a staunch supporter of the war effort, he opposed the destruction of slavery. Not only had he just voted against the amendment—he had vehemently denounced it. Holman, as Ashley viewed him, was thus one of the “devil’s disciples.” He was beyond redemption. And with this in mind, Ashley set about to find at least eleven additional House members who would stand their ground against men like Holman.

Copyright notice: Excerpted from Who Freed the Slaves?: The Fight over the Thirteenth Amendment by Leonard L. Richards, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2015 by University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)