The Chieftain and the Chair

The Rise of Danish Design in Postwar America

9780226550329

9780226550466

The Chieftain and the Chair

The Rise of Danish Design in Postwar America

Publication supported by the Neil Harris Endowment Fund

A history of how Danish design rose to prominence in the postwar United States, becoming shorthand for stylish modern comfort.

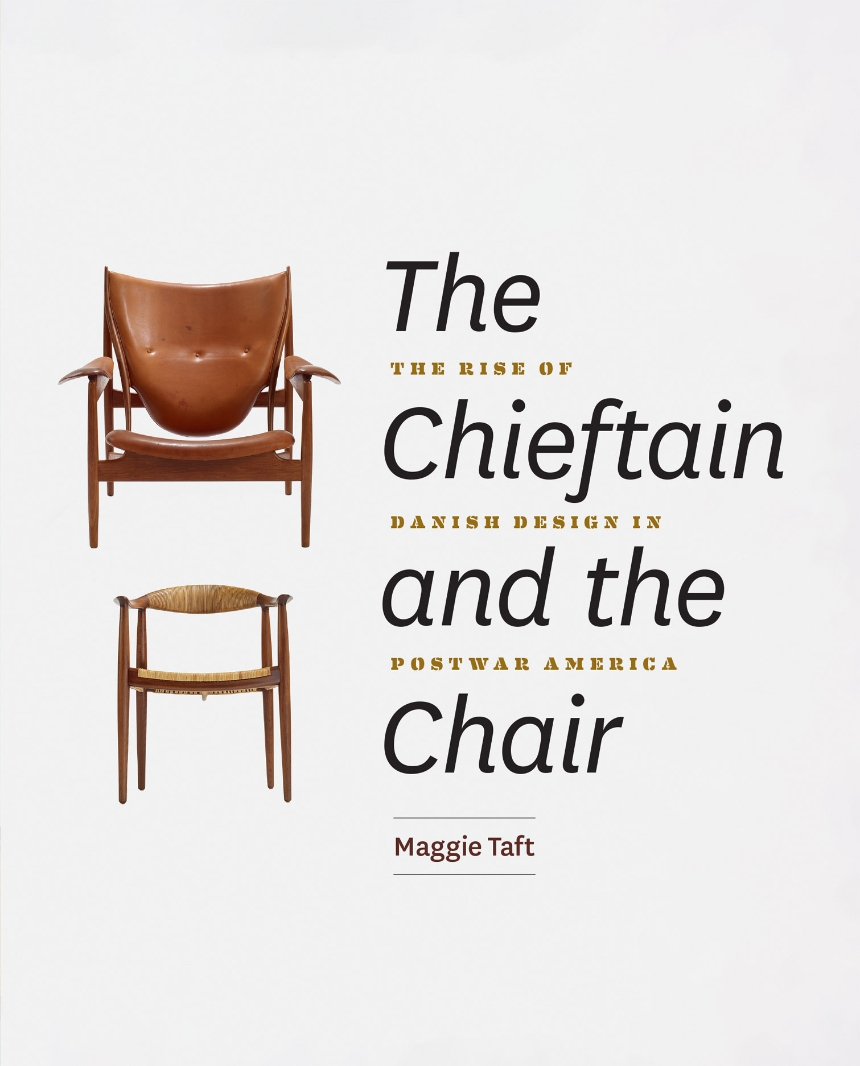

Today, Danish Modern design is synonymous with clean, midcentury cool. During the 1950s and ‘60s, it flourished as the furniture choice for Americans who hoped to signal they were current and chic. But how did this happen? How did Danish Modern become the design movement of the times? In The Chieftain and the Chair, Maggie Taft tells the tale of our love affair with Danish Modern design. Structured as a biography of two iconic chairs—Finn Juhl’s Chieftain Chair and Hans Wegner’s Round Chair, both designed and first fabricated in 1949—this book follows the chairs from conception and fabrication through marketing, distribution, and use.

Drawing on research in public and private archives, Taft considers how political, economic, and cultural forces in interwar Denmark laid the foundations for the postwar furniture industry, and she tracks the deliberate maneuvering on the part of Danish creatives and manufacturers to cater to an American market. Taft also reveals how American tastemakers and industrialists were eager to harness Danish design to serve American interests and how furniture manufacturers around the world were quick to capitalize on the fad by flooding the market with copies.

Sleek and minimalist, Danish Modern has experienced a resurgence of popularity in the last few decades and remains a sought-after design. This accessible and engaging history offers a unique look at its enduring rise among tastemakers.

Today, Danish Modern design is synonymous with clean, midcentury cool. During the 1950s and ‘60s, it flourished as the furniture choice for Americans who hoped to signal they were current and chic. But how did this happen? How did Danish Modern become the design movement of the times? In The Chieftain and the Chair, Maggie Taft tells the tale of our love affair with Danish Modern design. Structured as a biography of two iconic chairs—Finn Juhl’s Chieftain Chair and Hans Wegner’s Round Chair, both designed and first fabricated in 1949—this book follows the chairs from conception and fabrication through marketing, distribution, and use.

Drawing on research in public and private archives, Taft considers how political, economic, and cultural forces in interwar Denmark laid the foundations for the postwar furniture industry, and she tracks the deliberate maneuvering on the part of Danish creatives and manufacturers to cater to an American market. Taft also reveals how American tastemakers and industrialists were eager to harness Danish design to serve American interests and how furniture manufacturers around the world were quick to capitalize on the fad by flooding the market with copies.

Sleek and minimalist, Danish Modern has experienced a resurgence of popularity in the last few decades and remains a sought-after design. This accessible and engaging history offers a unique look at its enduring rise among tastemakers.

Reviews

Excerpt

1955. Plano, Illinois. Alongside the Fox River, in a tree-lined clearing, a glass house hovers on stilts. Inside, a pair of Hans Wegner’s Round Chairs dresses the ends of a dining table set for six (fig. 0.1). The chairs’ gentle contours stand in contrast to the right angles of the building’s planes, yet their silhouettes echo the transparency of the floating glass walls. Light streams through their open teakwood frames and cane seats. An ocean away from Denmark, where they were designed and made, the chairs seem at home.

When Dr. Edith Farnsworth chose Wegner’s Round Chair—often called simply “the Chair”—for this prominent place in the country retreat Ludwig Mies van der Rohe had designed for her, refusing the tubular steel and leather pieces of his own design that he proposed, she was but one of many Americans embracing the midcentury fad for Scandinavian design. Danish design, in particular, became so popular that American manufacturers sought to capitalize on its cachet. As Danish furniture exports to the United States climbed over the course of the 1950s, American furniture companies hired Danes to design lines of modern furnishings. Some companies even referenced the craze in their names. Dansk, for example, was not a Danish company but an American one, which sometimes hired Danes to design its dinner- and cookware. Lifestyle editors featured Danish design in full-color magazine spreads, and “Danish” became shorthand for a livable, modern style associated with natural materials, quality craftsmanship, and casual comfort. (...)

Though “Danish design” appears to describe a national style, it is not interchangeable with midcentury design from Denmark. Period participants in the furniture industry understood this, even as they benefited from the publicity and growth in sales that the term and its associated aesthetic produced. “We cannot say that a Danish taste of furnishing is existing,” one prominent furniture maker told an Italian journalist in 1955, as Danish furniture exports skyrocketed.3 Americans and other foreigners, he argued, were conflating all of Denmark’s production with one small, Copenhagen-based sliver of the industry; furniture like Wegner’s Chair, though seen as representative of Danish design at large, existed alongside industrial design and folk art, neohistoricist homage and Viking-inspired kitsch. But the Italian journalist was skeptical of the furniture maker’s protest. “Danish taste must exist,” he wrote, “for the simple reason that millions of persons are convinced of its existence.”

The Danish furniture maker was not wrong in insisting that Denmark had no single, unified design identity—that its overseas exports represented neither the full range of Danish design production nor a design style embraced by all of Denmark’s nearly 4.5 million midcentury inhabitants. Nonetheless, as the Italian reporter countered, widespread belief in the idea of Danish design was enough to make it real. The version of Danish design embraced by Americans, in the postwar era and today, may have been a fiction, but its emergence as something recognizable and powerful shaped design culture and popular taste worldwide. How did this happen, and why?

The Chieftain and the Chair answers these questions by following two iconic designs—Finn Juhl’s Chieftain Chair and Hans Wegner’s Round Chair—from their conception and fabrication in Denmark to their popularization and reproduction in the United States (plates 1 and 2). The Chieftain was, as described in the New York Times, one of the “status chairs” of the 1950s. And the Chair was a media darling, appearing in a variety of contexts, including magazine features on interior design and the first televised presidential debate. The Chieftain and the Chair are both notable design achievements, as well. Though the Chieftain’s size makes it something of an outlier in a category typified by small, limber designs, its biomorphic form is emblematic of what House Beautiful called the “soft, rounded flowing forms” of Danish design. With its wooden frame suspending its upholstered seat back and armrests, it also exemplifies a structural technique often deployed by Juhl to produce a floating effect. The joinery of Wegner’s Chair is innovative, with its unbroken top rail transitioning into armrests and elegant finger joints providing structural strength that eliminates the need for a supporting backboard.

Even so, the two chairs are less exceptional than exemplary products of Danish design in the postwar period. Their stories help to show how Danish design’s popularization was the product not simply of creative genius, but of institutions, designers, fabricators, distributors, professional and amateur tastemakers, and, perhaps most surprisingly, copyists, who together brought the very idea of Danish design into existence. This diffuse activity is not unique to Danish design; understanding design history requires attending to the contexts that give shape to objects, the conditions of their manufacture, the circumstances of their circulation, and how they are taken up by the market and by consumers. Here, the Chieftain and the Chair, two familiar designs, tell the particular story of Danish Modern’s invention and rise in postwar America.

When Dr. Edith Farnsworth chose Wegner’s Round Chair—often called simply “the Chair”—for this prominent place in the country retreat Ludwig Mies van der Rohe had designed for her, refusing the tubular steel and leather pieces of his own design that he proposed, she was but one of many Americans embracing the midcentury fad for Scandinavian design. Danish design, in particular, became so popular that American manufacturers sought to capitalize on its cachet. As Danish furniture exports to the United States climbed over the course of the 1950s, American furniture companies hired Danes to design lines of modern furnishings. Some companies even referenced the craze in their names. Dansk, for example, was not a Danish company but an American one, which sometimes hired Danes to design its dinner- and cookware. Lifestyle editors featured Danish design in full-color magazine spreads, and “Danish” became shorthand for a livable, modern style associated with natural materials, quality craftsmanship, and casual comfort. (...)

Though “Danish design” appears to describe a national style, it is not interchangeable with midcentury design from Denmark. Period participants in the furniture industry understood this, even as they benefited from the publicity and growth in sales that the term and its associated aesthetic produced. “We cannot say that a Danish taste of furnishing is existing,” one prominent furniture maker told an Italian journalist in 1955, as Danish furniture exports skyrocketed.3 Americans and other foreigners, he argued, were conflating all of Denmark’s production with one small, Copenhagen-based sliver of the industry; furniture like Wegner’s Chair, though seen as representative of Danish design at large, existed alongside industrial design and folk art, neohistoricist homage and Viking-inspired kitsch. But the Italian journalist was skeptical of the furniture maker’s protest. “Danish taste must exist,” he wrote, “for the simple reason that millions of persons are convinced of its existence.”

The Danish furniture maker was not wrong in insisting that Denmark had no single, unified design identity—that its overseas exports represented neither the full range of Danish design production nor a design style embraced by all of Denmark’s nearly 4.5 million midcentury inhabitants. Nonetheless, as the Italian reporter countered, widespread belief in the idea of Danish design was enough to make it real. The version of Danish design embraced by Americans, in the postwar era and today, may have been a fiction, but its emergence as something recognizable and powerful shaped design culture and popular taste worldwide. How did this happen, and why?

The Chieftain and the Chair answers these questions by following two iconic designs—Finn Juhl’s Chieftain Chair and Hans Wegner’s Round Chair—from their conception and fabrication in Denmark to their popularization and reproduction in the United States (plates 1 and 2). The Chieftain was, as described in the New York Times, one of the “status chairs” of the 1950s. And the Chair was a media darling, appearing in a variety of contexts, including magazine features on interior design and the first televised presidential debate. The Chieftain and the Chair are both notable design achievements, as well. Though the Chieftain’s size makes it something of an outlier in a category typified by small, limber designs, its biomorphic form is emblematic of what House Beautiful called the “soft, rounded flowing forms” of Danish design. With its wooden frame suspending its upholstered seat back and armrests, it also exemplifies a structural technique often deployed by Juhl to produce a floating effect. The joinery of Wegner’s Chair is innovative, with its unbroken top rail transitioning into armrests and elegant finger joints providing structural strength that eliminates the need for a supporting backboard.

Even so, the two chairs are less exceptional than exemplary products of Danish design in the postwar period. Their stories help to show how Danish design’s popularization was the product not simply of creative genius, but of institutions, designers, fabricators, distributors, professional and amateur tastemakers, and, perhaps most surprisingly, copyists, who together brought the very idea of Danish design into existence. This diffuse activity is not unique to Danish design; understanding design history requires attending to the contexts that give shape to objects, the conditions of their manufacture, the circumstances of their circulation, and how they are taken up by the market and by consumers. Here, the Chieftain and the Chair, two familiar designs, tell the particular story of Danish Modern’s invention and rise in postwar America.